Sapsiwai - Fotolia

Researchers argue action bias hinders incident response

A Black Hat 2021 session focused on the human instinct to act immediately after a cyber attack and how that can negatively impact incident response.

The best approach to incident response following a cyber attack isn't to jump right in, but to slow down.

That was the theme of a Black Hat 2021 session Thursday where Josiah Dykstra, technical fellow at the National Security Agency's cybersecurity collaboration center, and Douglas Hough, senior associate at the John Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, presented a less traditional approach to incident response. Based on concepts in behavioral economics and behavioral psychology, the pair determined that rapid response isn't always the best response when it comes to cybersecurity.

The main concern they observed was action bias. According to Hough, action bias is the impulse to act in order to gain a sense of control over a situation. He provided an example of a study done on soccer goalkeepers in Europe and Israel, which examined how they moved during the high-stakes situation of penalty kicks. According to the study, 95% of the time the goalkeepers moved either left or right even though the optimal strategy, based on statistical evidence, is to stay in the middle.

Whether it's on the soccer field or during an incident response situation, the cause of action bias is fairly simple.

"It's the urgency to take some action. It's to show leadership. It's to prevent second-guessing," Hough said during the session.

Looking at action bias in terms of cybersecurity, Dykstra referred to the example of ransomware, breaking it down into three groups during an incident response engagement: users, cybersecurity defenders and leaders. Though the goals of each group differed, they do share a commonality. Dykstra and Hough found that all three groups had an instinct to get some control over the situation, and they acted on that instinct.

"Even though their actions looked differently, none of them wanted to just passively stand by and gather more information or to build on a plan they had made early in advance," Dykstra said during the session. "And there was pressure to act like ransomware often has a countdown, and if you don't take action, bad things happen. And so, that time pressure encouraged people to take any and all possible actions."

Examples of this are present in recent ransomware attacks including both the Colonial Pipeline Co. and JBS Foods USA, where both companies were quick to give into ransom demands. In a press release from JBS, the subsidiary of the world's largest beef producers admitted that it paid an $11 million ransom, even though "at the time of payment, a vast majority of the company's facilities were operational."

During two different congressional hearings in June, James Blount, Colonial Pipeline CEO, provided further details about the attack. First, he confirmed that the company paid a $4.4 million ransom on May 8, one day after the attack. Secondly, he revealed that just days after the attack, the company learned that it could have restored data from backups. As it turned out, they were not corrupted.

Returning to those three distinct groups, Dykstra said, in the case of a ransomware attack they went with an immediate, non-analysis action. Besides paying ransoms, those actions sometimes include shutting down networks completely to stop the spread of ransomware, but Dykstra argued against such actions. "In the middle of a crisis, the best action is almost never to pull the plug," he said. "There are better, smarter things we can do."

For the CISO of a company, or any other leadership in an organization, Dykstra said their job depends on security, and ransomware is a failure of security. In some sense, he said, people get fired in these situations.

"The CISO's real goal in life is, ultimately, security, even if it requires crazy amounts of resources [and] lots of money or time. They want zero ransomware," Dykstra said.

Setting a goal that attacks will never happen again is dangerous, according to Hough. He cited three reasons for that danger. Most notably, it encourages people to try anything and everything to stop it from happening it again, which can lead to wrongful spending of resources. Assuming it can never happen makes for an unachievable goal that only adds needless stress on the workforce.

"The attackers are motivated to keep attacking. Nothing that we can do will ever be 100% successful, and 'never again' sets this unprecedented goal that we can be 100% successful when, in fact, the attackers will keep attacking," Dykstra said.

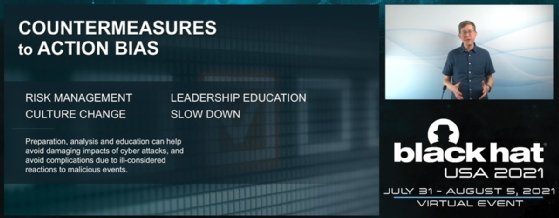

The biggest solution, according to Hough and Dykstra, is to slow down the incident response process; although, slowing down doesn't mean doing nothing. Dykstra advised moving the time security teams devote to a problem to before the crisis occurs by way of incident response planning, tabletop exercises, red teaming and other types of preparation. He also said he believes it's important to have healthy skepticism in the heat of the moment, particularly when someone asks if something should be done in response to a data breach.

"Ask yourself, 'Is that going to have the benefits that I think it's going to, and at what cost?'" Dykstra said. "You know the phrase in shooting, 'Ready, aim, fire.' It feels like in cybersecurity, too often, we fire first, and then maybe it's ready, and then maybe it's aim."

Being aware of action bias is just a first step, the presenters said. Preparation and practice are two key factors that Dykstra said can lead to both consistent and more rational actions. "Have a plan, practice the plan and be prepared for the unexpected, because we can't anticipate everything that's going to happen, particularly in cybersecurity."