Yuichiro Chino/Moment via Getty

Exploring the Fundamentals of Medical Billing and Coding

Medical billing and coding are the backbone of the healthcare revenue cycle, ensuring payers and patients reimburse providers for services delivered.

Medical billing and coding translate a patient encounter into the languages healthcare facilities use for claims submission and reimbursement.

Billing and coding are separate processes, but both are necessary for providers to receive payment for healthcare services.

Medical coding involves extracting billable information from the medical record and clinical documentation, while medical billing uses those codes to create insurance claims and bills for patients. Creating claims is where medical billing and coding intersect to form the backbone of the healthcare revenue cycle.

The process starts with patient registration and ends when the provider receives full payment for all services delivered to patients.

The medical billing and coding cycle can take anywhere from a few days to several months, depending on the complexity of services rendered, claim denial management, and how organizations collect a patient’s financial responsibility.

Ensuring healthcare organizations understand the fundamentals of medical billing and coding can help providers and other staff operate a smooth revenue cycle and recoup all the allowable reimbursement for quality care delivery.

WHAT IS MEDICAL CODING?

Medical coding starts with a patient encounter in a physician’s office, hospital, or other healthcare facility. When a patient encounter occurs, providers detail the visit or service in the patient’s medical record and explain why they delivered specific services, items, or procedures.

Accurate and complete clinical documentation during the patient encounter is critical for medical billing and coding, AHIMA explains. The golden rule of healthcare billing and coding departments is, “Do not code it or bill for it if it’s not documented in the medical record.”

Providers use clinical documentation to justify reimbursements to payers when a conflict with a claim arises. If a provider does not sufficiently document a service in the medical record, the organization could face a claim denial and potentially a write-off.

Providers could also face a healthcare fraud or liability investigation if they attempt to bill payers and patients for services incorrectly documented in the medical record or missing from the patient’s data altogether.

Once a patient leaves the healthcare facility, a professional medical coder reviews and analyzes clinical documentation to connect services with billing codes related to a diagnosis, procedure, charge, and professional and/or facility code.

Coders use the following code sets during this process.

ICD-10 DIAGNOSIS CODES

Diagnosis codes are key to describing a patient’s condition or injury, as well as social determinants of health and other patient characteristics. The industry uses the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) to capture diagnosis codes for billing purposes.

ICD-10-CM (clinical modification) codes classify diagnoses in all healthcare settings, while ICD-10-PCS (procedure coding system) codes are for inpatient services at hospitals.

ICD codes indicate a patient’s condition, the location and severity of an injury or symptom, and if the visit is related to an initial or subsequent encounter.

There are more than 70,000 unique identifiers in the ICD-10-CM code set alone. The World Health Organization (WHO) maintains the ICD coding system, which is used internationally in modified formats.

CPT AND HCPCS PROCEDURE CODES

Procedure codes complement diagnosis codes by indicating what providers did during an encounter. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) make up the procedure coding system.

The American Medical Association (AMA) maintains the CPT coding system, which describes the services rendered to a patient during an encounter for private payers. AMA publishes CPT coding guidelines each year to support medical coders with coding-specific procedures and services.

CPT codes have modifiers that describe the services in greater specificity. CPT modifiers indicate if providers performed multiple procedures, the reason for a service, and where on the patient the procedure occurred. Using CPT modifiers helps ensure providers receive accurate reimbursement for all services.

While private payers tend to use CPT codes, CMS and some third-party payers require providers to submit claims with HCPCS codes. The Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requires organizations to use HCPCS codes in certain cases.

Many HCPCS and CPT codes overlap, but HCPCS codes describe non-physician services, such as ambulance rides, durable medical equipment, and prescription drug use. CPT codes only indicate the procedure, not the items a provider used.

HSPCS codes also have modifiers that help specify services further.

CHARGE CAPTURE CODES

Coders connect physician order entries, patient care services, and other clinical items with a chargemaster code. A chargemaster is a collection of standard prices for services and items that a provider organization offers.

Charge capture codes may include procedure descriptions, time reference codes, departments involved in the medical service, and billable items and supplies.

The CMS Hospital Price Transparency rule requires hospitals to publish their chargemasters on their website and display the prices of 300 shoppable services.

In a process known as charge capture, revenue cycle management leaders use these prices to negotiate claims reimbursement rates with payers. Coders submit the codes and corresponding charges to the payers, and then providers bill patients for the remaining balance.

PROFESSIONAL AND FACILITY CODES

When applicable, medical coders also translate the medical record into professional and facility codes.

Professional codes capture physician and other clinical services delivered and connect the services with a code for billing. These codes stem from the documentation in a patient’s medical record.

On the other hand, hospitals use facility codes to account for the cost and overhead of providing healthcare services. These codes capture the charges for medical equipment, supplies, medication, nursing staff, and other technical care components.

Hospitals can include professional codes on claims when a provider employed by the hospital performs clinical services. However, if a non-hospital provider uses the hospital’s space and supplies, the facility cannot include a professional code.

Integrating professional and facility coding into one platform may help facilitate the process for hospitals. Leveraging technology, such as computer-assisted coding (CAC) solutions, can help speed up the medical coding process and increase coding accuracy and efficiency, according to AHIMA.

WHAT IS MEDICAL BILLING?

Medical billing is the process by which healthcare organizations submit claims to payers and bill patients for their own financial responsibility. While coders are busy translating medical records, the front-end billing process has already started.

FRONT-END MEDICAL BILLING

Medical billing begins when a patient registers at the office or hospital and schedules an appointment.

During pre-registration, administrative staff members ensure patients complete required forms and confirm patient information, including home address and insurance coverage. After verifying that the patient’s health plan will cover the requested services and submitting any prior authorizations, staff should confirm patient financial responsibility.

During the front-end medical billing process, staff informs patients of any costs they are responsible for. Ideally, the office can collect any copayments from the patient at the appointment.

Once a patient checks out, medical coders obtain the medical records and begin to turn the information into billable codes.

BACK-END MEDICAL BILLING

Together, medical coders and back-end medical billers use codes and patient information to create a “superbill,” according to AAPC.

The superbill is an itemized form that providers use to create claims. The form typically includes:

- Provider information: rendering provider name, location, and signature, as well as name and National Provider Identifier (NPI) of ordering, referring, and attending physicians

- Patient information: name, date of birth, insurance information, date of first symptom, and other patient data

- Visit information: date of service(s), procedure codes, diagnosis codes, code modifiers, time, units, quantity of items used, and authorization information

Providers may also include notes or comments on the superbill to justify medically necessary care. Billers pull information from the superbill to prepare claims.

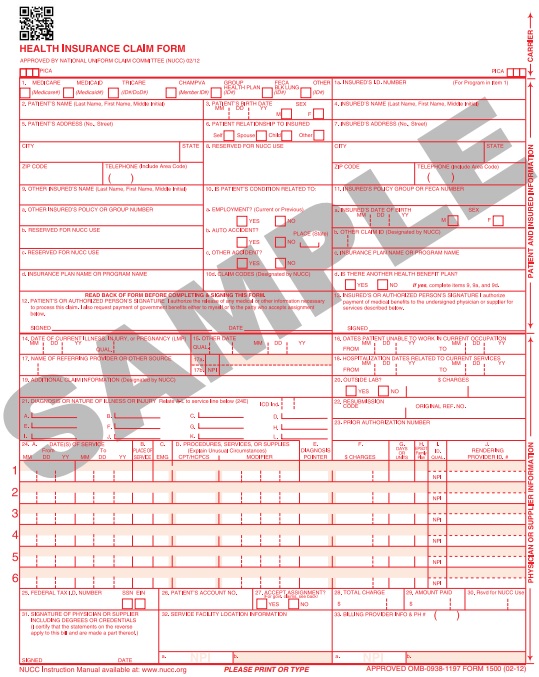

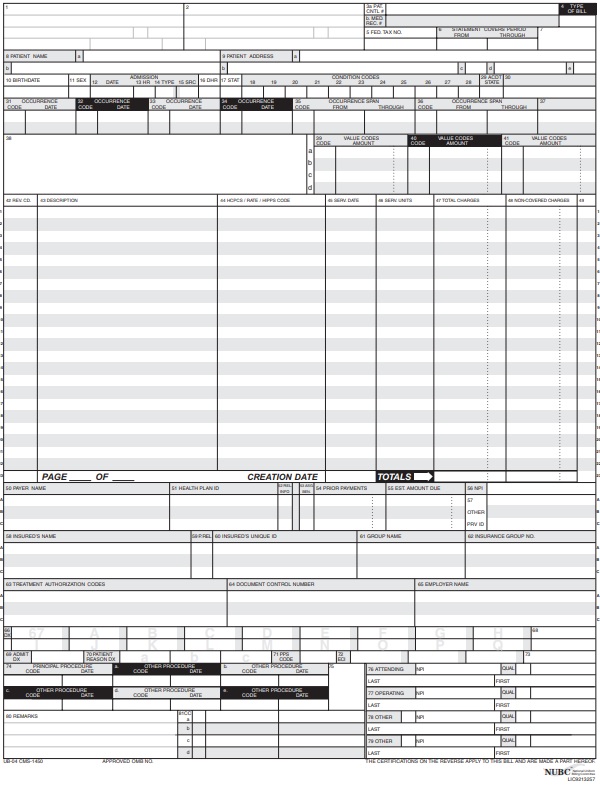

Billers tend to deal with two types of claim forms. Medicare created the CMS-1500 form for non-institutional healthcare facilities, such as physician practices, to submit claims. The federal program also uses the CMS-1450, or UB-04, form for claims from institutional facilities, such as hospitals.

Private payers, Medicaid, and other third-party payers may use different claim forms based on their specific requirements for claim reimbursement. Some payers have adopted the CMS-generated forms, while others have based their unique forms on the CMS format.

During claim preparation, billers “scrub” claims to ensure that procedure, diagnosis, and modifier codes are present and accurate and that necessary patient, provider, and visit information is complete and correct.

Then, back-end medical billers transmit claims to payers. Under HIPAA, providers must submit their Medicare Part A and B claims electronically using the ASC X12 standard transmission format, commonly known as HIPAA 5010.

Other payers have followed in Medicare’s footsteps by requiring electronic transmission of claims. According to CAQH, electronic claims management adoption could save providers around $9.5 billion per year.

The shift to remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted more payers and providers to adopt electronic claims management systems.

Medical billers submit claims directly to the payer or use a third-party organization, such as a clearinghouse. A clearinghouse forwards claims from providers to payers. These companies also scrub claims and verify the information to ensure reimbursement.

Clearinghouses may help providers who do not have access to a comprehensive practice management system to edit and submit claims electronically. Clearinghouses can help reduce potential errors stemming from manual processes.

Once a claim makes its way to the payer, adjudication begins. During adjudication, the payer will assess a provider’s claim and determine how much it will pay the provider. Payers can accept, deny, or reject claims.

Payers send Electronic Remittance Advice (ERA) forms back to the provider organization explaining what services received reimbursement, if additional information is needed, and the reason for rejecting or denying a claim. Depending on the reason, billers can correct and resubmit the claims for reimbursement.

After receiving reimbursement for a successful claim, medical billers create statements for patients. Providers will typically charge patients the difference between the rate on their chargemaster and what the payer reimbursed.

Traditionally, if a patient received care at an out-of-network provider, it was the patient’s responsibility to negotiate out-of-pocket expenses with the health plan. However, under the No Surprises Act, which went into effect on January 1, 2022, providers must submit a claim to the health plan for out-of-network services to see if the payer will provide coverage.

The policy calls for providers to comply with new claims submission requirements and communicate with out-of-network plans. Payers and providers have 30 days after a claim is submitted to negotiate the price for a surprise bill. If they cannot agree, they must go through an independent dispute resolution process to determine the payment rate.

The final phase of medical billing is patient collections. Medical billers collect patient payments and submit the revenue to accounts receivable (A/R) management, where payments are tracked and posted.

Some patient accounts may land in “aging A/R,” which indicates that patients have failed to pay their patient financial responsibility, typically after 30 days. Medical billers should follow up with patient accounts in aging A/R batches to remind patients to pay their bills and ensure the organization receives the revenue.

Revenue cycle management automation has helped some practices boost A/R management efficiency, including staff productivity and workflows.

Once a medical biller receives the total balance of a patient’s financial responsibility and payer reimbursement for a claim, they can close the patient account and conclude the medical billing and coding cycle.

HOW COVID-19 IMPACTED MEDICAL BILLING AND CODING

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted several changes to medical billing and coding processes.

For example, in 2020, electronic claims management adoption increased by 2.3 percentage points across the medical and dental industries. In the medical industry, those transactions included eligibility and benefit verification, prior authorization, claim submission, claim status inquiry, claim payment, and remittance advice.

Medical billers and coders had to determine new codes and reimbursement policies with the emersion of a new virus.

In March 2020, the WHO created the first ICD-10 code for COVID-19. Since then, there have been at least a dozen new ICD procedure codes related to the virus and many more changes to CPT and HCPCS codes to document COVID-19 and related conditions.

CMS also made a significant change to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule during the pandemic that impacted medical billers and coders. The new guidelines stated that physicians could select an evaluation and management (E/M) code based on the total time spent on the date of the patient encounter instead of relying on a patient’s history or physical exam to determine appropriate E/M coding.

Medical billing and coding are integral healthcare revenue cycle processes. Ensuring that the medical billing and coding cycle run smoothly ensures that providers get paid for services delivered, and provider organizations remain open to deliver care to patients.

This article was originally published on June 15, 2018.