KOHb - Getty Images

Software development in 2026: A hands-on look at AI agents

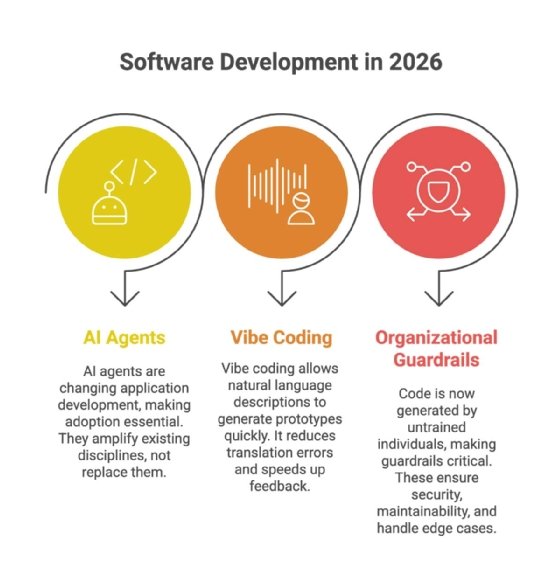

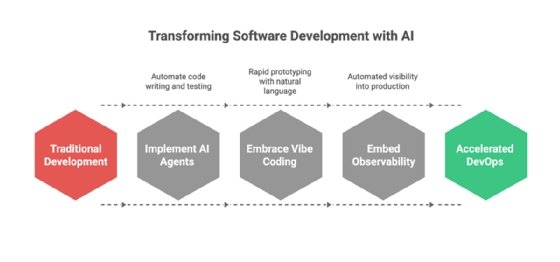

The agentic workflows that software teams are transitioning to in 2026 are fundamentally changing the economics of writing, testing and releasing code.

AI agents and generative AI have changed application development forever.

This is not marketing hyperbole. The shift underway is structural, irreversible and already visible in day-to-day coding practice. Adopting these technologies is neither optional nor something organizations can approach gradually in baby steps.

Just as jet engines did not merely make propeller aircraft faster but fundamentally rewrote the economics of range, scale and airline viability, and just as transistors did not simply improve vacuum tubes but enabled entirely new classes of electronics, the agentic workflows software teams are transitioning to in 2026 fundamentally change the economics of writing, testing and releasing code.

It is critical to understand that agentic AI is an amplifier of existing technical and organizational disciplines, not a substitute for them. Organizations with strong foundations in software engineering practices, GitOps, CI/CD, test automation, platform engineering and architectural oversight can channel agent-driven velocity into predictable productivity gains. Organizations without these foundations will simply generate chaos quicker, as AI agents are indifferent to whether they are scaling good practices or bad ones.

In this article, I'll illustrate both sides of this transformation, showing the productivity gains and new issues that arise with agentic vibe coding. Pending the development of artificial general intelligence, human coders must still take full responsibility for the effect of their project code.

Harnessing AI agents

The following is a concrete, representative example of a modern agentic coding system. It is broadly consistent with what developers will encounter across this emerging class of tools.

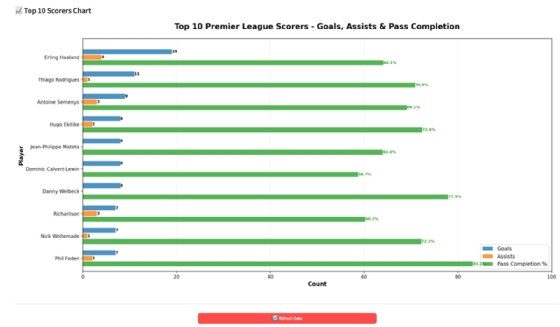

In this example, I asked Cursor's Composer 1 agent model to create a quick dashboard app that shows the top 10 goal scorers in the Premier League in the 2025/26 season using a free API.

Starting prompt and initial steps

Below is the initial prompt I used to kick off the project:

Create an app that uses the football-data.org API to build a bar chart for the top 10 goal scorers in the Premier League this season that shows two values for each scorer: total number of goals and total number of assists. Use Streamlit as the frontend and begin by creating a requirements document for my approval.

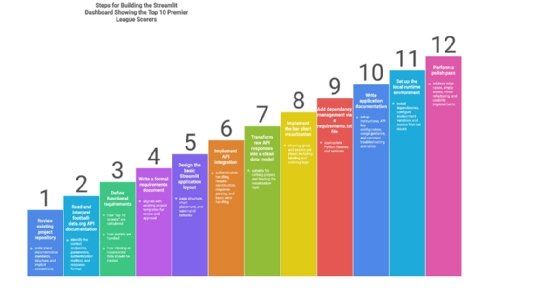

Here are the initial steps the agent took:

- Analyze the files already in the project repository to learn about my preferences and company policies. The project repository already includes requirements documentation files for two other projects, which constitute an ideal template for this new project.

- Review the football-data.org documentation to find the API endpoint and query parameters required for retrieving the requested player stats.

- Create the requirements document and pause for my review.

The requirements document replicated the format and level of detail of the other requirements documents in the project repository. It clearly outlined the API parameters required to determine the top scorers, extracting their details, and validating and visualizing the data. It incorporated the Python-native Streamlit frontend and listed all the further libraries it proposed using. It also showed where it planned to store the API key.

Once I approved these requirements, the agent created the Streamlit application in under one minute, including a requirements.txt file listing all Python dependencies and a documentation page with setup instructions, a user guide, troubleshooting tips and details on the API's inner workings. Instead of following the setup instructions, I asked the agent to set up the application for me. Within minutes, the bar chart of the current top 10 Premier League scorers appeared in the default browser via the expected minimalistic Streamlit app.

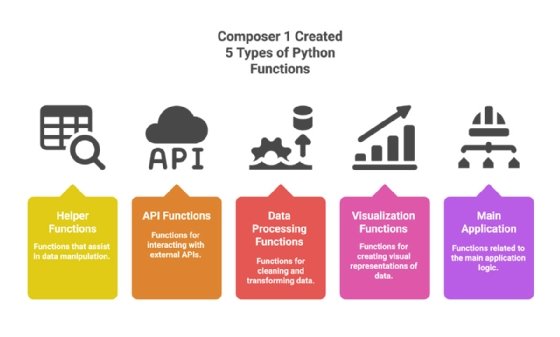

Scrutinizing the code

Upon review, the initial code appears to be well organized and logically structured into functions that are responsible for a specific single purpose such as data handling, API integration, data visualization and the main application.

There is comprehensive documentation inline and in a separate document, good error handling, data validation before use and use of the appropriate code libraries.

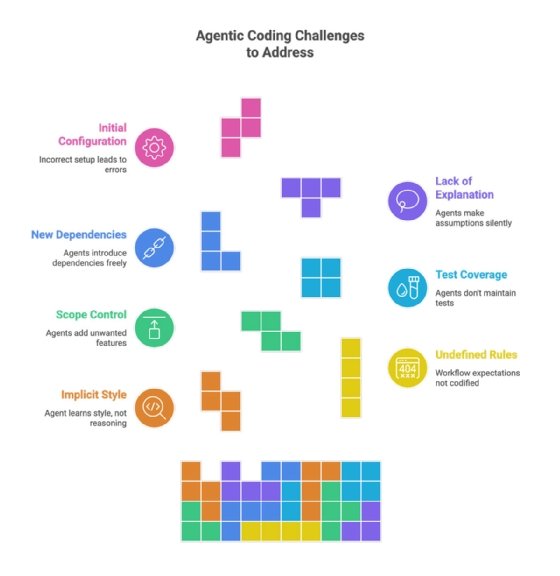

Tests were missing

There were no tests of any kind included, despite the other apps in this same project having well-documented unit, integration and system tests attached to them. I asked the agent to create the required test suite and it returned 22 tests covering all important aspects of this small application and updated the documentation accordingly.

Container app was not in sync

I decided that I wanted to be able to deploy the app as a container to Docker Desktop for easy sharing. The agent created the required Docker file and provided the build and run commands for the resulting container. After verifying that the app ran successfully in the container, I requested that the agent remove the extra table it had created under the scorer chart and move the ugly red refresh button to the bottom. This only took a few seconds. However, it forgot to update the containerized version of the application, leading to a temporary state of confusion on my end, as I was using the containerized version for review. Once I pointed out the issue, the agent nicely updated the file and opened the app for me to look at. At this time, the app was ready to go.

Multiple hours saved

Depending on a developer's familiarity with Streamlit and the project's parameters, this workflow would typically take several hours rather than 10 minutes, highlighting that the real acceleration from agentic tooling comes not from faster typing but from collapsing the surrounding "glue work" of a given project into minutes.

The agent adds a trap door

I decided that we need to also show the percentage of completed passes for our 10 top goal scorers and make the request accordingly. The agent updated the code and opened the app for me to review. I was amazed at how quickly it figured this out, as there was now a pass completion percentage next to each goal scorer. But then I looked at the Python code and noticed that all these values were hardcoded and completely fictional, instead of coming from an API query.

We have to talk

I asked the agent why it would just make up data. It tells me that the API endpoint it used does not offer the pass completion percentage statistic. It explained that it used sample data to show what this data would look like had it been available. This was a weak excuse not even worthy of an intern. This is exactly why human developers must be responsible for every line of automatically generated code, to prevent the risk of releasing an application that includes fictional data.

Figuring it out

I then asked what the options were for actually implementing the requested feature so that it pulls from a live data source. The agent told me that I need to either:

- use a different API,

- scrape data from websites that publish these statistics, or

- keep the sample data, but clearly label it as such.

These are interesting suggestions, but from experience, I knew that web scraping to create structured data can be brittle. I asked for a recommendation and the agent told me five good reasons why I should go with sample data. It provided reasons why consolidating multiple data sources is too complex, mentioned legal considerations and recommended an approach that scrapes data but falls back on sample data in case this approach fails. Considering that I promised my fictional boss a working prototype of this application, I brushed aside my concerns about the issues of web scraping and gave the go ahead.

The struggle of getting it all to work

The agent tells me that it's done with the implementation of the new feature. I inquired about how the unit and regression tests went. It turned out that none of those happened. I asked to add and run these tests, but no pass completion data came back. The agent then iterated through different Python libraries to solve the issue, concluded that CloudFlare blocked the data retrieval, then immediately started "updating the scraper to handle this issue." As none of the code revisions worked, it asked to go through the local Chrome browser.

That’s when we ran into the next serious issue. It tells me that it successfully retrieved the passing percentage data. I ignore the lack of updated test suite and run the Docker file. It remembers to add Chrome as a dependency to the Docker file. After running the app, I see all pass completion figures, but their bars -- in some cases -- overlap with one of the other bars. The agent tells me it fixed the issue and updated the container, but I see no changes and ask it to test it instead of making me test it. Again, it tells me it's fixed and reuploaded, but now it looks worse. After two more iterations, it works, and I must, again, ask for the new feature to be added to the test suites. It runs the updated tests and they all pass. Just to be safe, I double check the data to see if everything checks out. It does -- the Top 10 Scorers chart is based on actual live data.

Agentic AI-based coding is without alternative

Even with all these revisions and refinements, the application was up and running in under 45 minutes. Manually completing all the required tasks would have taken close to a complete workday for one developer. In a world where organizations increasingly compete through their ability to develop better software products for their customers in a cost-effective manner, leaving performance gains of this magnitude on the table is not a viable option.

Key takeaways for agentic coding

Agents learn from your codebase the way a new team member would -- picking up naming conventions, preferred libraries, documentation style and how similar problems were solved before. The more mature and consistent your codebase, the better the agent adapts. But the agent doesn't learn why your team does things a certain way, only that it does. Style is implicit while discipline is explicit.

1. Define explicit rules

Workflow expectations still need to be codified in instructions such as "always test, update the documentation and the container image, before declaring a task done." These are rules that agents cannot infer simply by looking at the codebase. They have to be spelled out, just as you'd document team standards for any new hire.

The same applies to scope control. Left to their own devices, agents will happily add features you didn't ask for -- gold-plate solutions with nice-to-have enhancements -- and introduce new dependencies or remove existing ones without warning. Establishing clear boundaries through concrete rules prevents the kind of drift that turns a simple feature request into a refactoring project.

2. Ensure test coverage

Testing discipline deserves particular attention. As the walkthrough showed, agents don't automatically maintain test coverage even when the rest of your codebase demonstrates that expectation. Require unit tests with any new function, run regression tests before declaring work complete and insist on edge case coverage rather than just happy paths. Documentation follows a similar pattern. Agents will produce inline comments and API documentation if asked, but keeping that documentation current as code evolves requires explicit instruction.

3. Require approval for new dependencies

Architecture decisions present a subtler challenge. Agents will generally follow existing patterns in a codebase, but they lack the context for why your team chose this pattern over that one, which past shortcuts caused production incidents, or what your users actually do versus what the requirements say. Before letting an agent introduce new dependencies or deviate from established approaches, require it to surface those decisions for human review.

4. Make the agent explain

Finally, establish clear communication norms. The agent should explain what it plans to do before doing it, surface uncertainties rather than making assumptions and report failures immediately rather than silently retrying or working around them. The sample data incident in the walkthrough, where the agent fabricated values rather than admitting the API couldn't provide them, illustrates why this matters.

5. Get the initial configuration right

Rules are only part of the picture. Cursor offers several configuration layers that determine not just what the agent should do, but what it's allowed to do and what happens after it acts. Model selection lets you match capability to task. Use Cursor's fast Composer model for routine work and switch to Claude or GPT for complex reasoning. Yolo mode allows the agent to execute terminal commands without approval. This is useful for running test suites autonomously but risky without guardrails. Command allow/deny lists let you block dangerous operations such as force pushes or recursive deletes from auto-execution. Model Context Protocol connections give the agent direct access to external tools and data sources, databases, APIs and documentation, reducing the copy-paste overhead that slows down context-heavy work.

The pattern here mirrors the broader thesis. Agents amplify whatever structure you put around them. The more mature your guardrails, the more safely you can let them run.

Torsten Volk is principal analyst at Omdia covering application modernization, cloud-native applications, DevOps, hybrid cloud and observability.

Omdia is a division of Informa TechTarget. Its analysts have business relationships with technology vendors.