Getty Images/iStockphoto

Fanout vs. choreography: Choosing system architecture

The fanout and choreography patterns are two common approaches to event-driven architecture, each offering its own advantages for modern distributed systems.

While the fanout pattern excels in broadcasting messages to multiple consumers through a decoupled and asynchronous mechanism, the choreography pattern enables communication between microservices by relying on event chains without a central controller. Understanding these patterns, their use cases and limitations is essential for designing scalable, reliable and efficient systems tailored to specific business needs.

This article explores both patterns in depth, providing insights into their applications, benefits and challenges, along with guidance on choosing the right architecture or adopting a hybrid approach.

What is the fanout pattern?

This is a one-to-many messaging pattern where a message is distributed or fanned-out to multiple downstream destinations. One way to implement this is to use a publish-subscribe (pub/sub) model, where a producer generates an event and sends it to a message broker, which then distributes it to all subscribed consumers. This communication is decoupled and asynchronous, with each consumer processing this event independently -- in parallel. The producer/publisher doesn't need to know the information it is broadcasting, so the subscribers don't need to know where the message comes from.

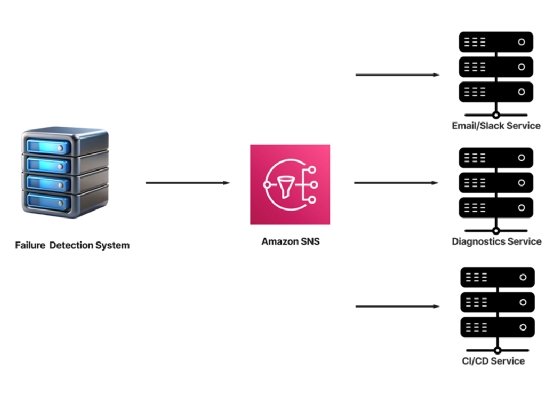

For example, let's say you have three services running in production, and suddenly one of them fails. As a good practice, you already have a failure detection system in place that runs three tasks once this happens:

- Send an email notification to members of the SRE/DevOps team.

- Run diagnostics on the issue.

- Stop all deployments in the CI/CD pipelines until the issue is resolved.

Now, instead of coupling these tasks all together with the failure detection system, we can launch a single failure event that would mirror the event to all three services.

Fanout systems are inherently stateless, which means that the event will only be delivered to active services that are directly subscribed to it. If any of the subscribed services are down, they will miss the event.

If you intend to use a stateful point-to-point model instead, the publisher -- failure detection system -- will be required to track connections with every consumer. Failure handling and retry logic will be handled in your code. This approach can quickly become overwhelming when the number of microservices grows.

A way to work around this is by introducing a persistent queue, such as Kafka, RabbitMQ or AWS SNS, in between. This will not only solve the problem of events going missing but also help manage the event lifecycle for each service independently.

Benefits

- Simplicity for broadcast scenarios. This approach is ideal for a straightforward notification to multiple relevant services.

- Reduced latency for read operations (fanout-on-write). For systems like Twitter (X) using fanout-on-write for timeline generation, data is pre-computed and distributed to all users' feeds at write time. This accounts for a faster read operation because the data is already available.

- Fault tolerance. Most message brokers in use persist messages in a way that ensures events are not lost even if the service/consumer is offline or down.

- High decoupling. This approach is spatial and temporal. Producers don't have direct knowledge of who, what and how many customers there are. Likewise, the consumers are only aware of the topic they are subscribed to. Being temporal means that the producer does not wait for consumers to process an event; it simply continues publishing, leading to non-blocking operations and an increase in overall system throughput.

Limitations

- Distributed error handling. With each consumer handling errors independently, creating a rollback -- or compensating action -- is not supported in the fanout pattern.

- No direct feedback mechanism. Fanout is asynchronous in nature. If a producer requires a synchronous response or some form of guarantee that all consumers have processed an event before proceeding with its logic, fanout by itself is not sufficient and would require introducing other patterns.

- Potential for overwhelm. Fanning out to too many consumers can often lead to an overload on the downstream systems, especially those with limited capacity -- such as API rate limits.

What is the choreography pattern?

This is a way for microservices to communicate with one another using events without a central controller telling them what to do. In this pattern no service directly calls the next. Instead, each service -- part of the workflow -- publishes an event when it has finished processing. The next process in line then continues this event and proceeds with the workflow until the entire workflow is finished.

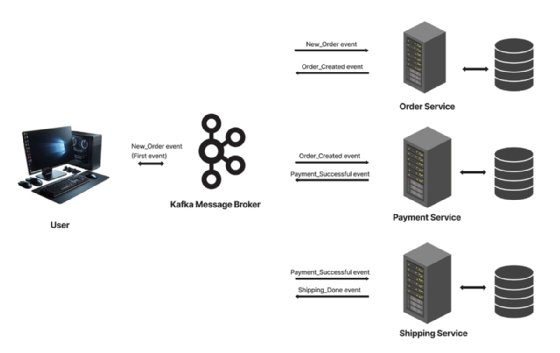

Let's consider this e-commerce example involving three services: Order, payment and shipping.

In the example:

- A customer places an order, triggering the first event, which is published to a topic or queue in the message broker.

- The order service, being subscribed to this event, listens for it, consumes it and gets it processed. The data gets saved, and an "order created" event is then pushed back into a message broker.

- The payment service subscribes to an "order created" event, consumes the event and then pushes a "payment successful" event back to the message broker.

- The shipping service scans for this event, pulls it, processes it and sends out a "shipping done" event to the broker. This can be sent to the client as a confirmation of the order and can still be consumed by other services, likely to update their workflows to done.

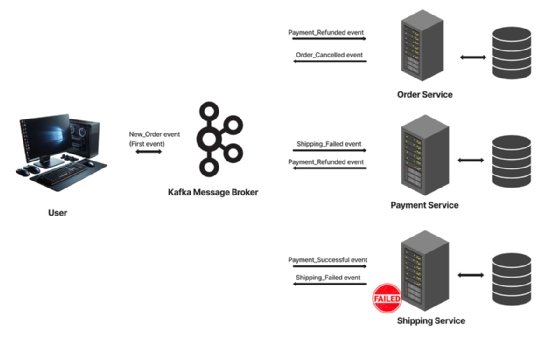

If anything goes wrong at any point -- let's say the shipping service fails to fulfil an order -- the shipping service will send out a negative event, prompting the entire workflow to be reverted using compensating transactions.

This negative event will be consumed by other services. For example, the payment service might consume it and respond by sending a "payment refund" event to the message broker, which the order service will then consume and inform the user that the order was cancelled.

Benefits

- Lightweight. This approach is perfect for simple workflows with two to three steps.

- Flexible. Adding new steps does not require modification to other existing services.

- Decentralized. No central broker means no single point of failure and performance bottleneck. As a result, when one service is down, the system will still function, but partially.

Limitations

- Implicit coupling. Although services are spatially decoupled, the reliance on emitted events and the expectation of subsequent events make them implicitly coupled. Any changes made to an event structure within one service will have a rippling effect and require coordination.

- Complex error handling. Configuring error handling -- such as rollbacks -- is complex, requiring every service to undo its part of a transaction.

- Consistency challenges. Maintaining consistent data across multiple systems is difficult since services operate independently. This can lead to race conditions, especially when making financial transactions.

- Lack of global process visibility. With choreography implemented, monitoring becomes difficult since there is no central place to view the state/progress of a particular transaction.

- Debugging overhead. Debugging failures, especially in a long chain of events, can pose a challenge to the team.

Choosing the right architecture

The decision between fanout and choreography depends on the specific requirements of the system.

When deciding, consider the following:

- System scale. Fanout is suited to large systems that contain many subscribed services/consumers that need the same event. For smaller autonomous systems, use choreography.

- Infrastructure constraints. If the team is comfortable with managing a central message broker, then fanout is the way to go; if not, consider the choreography pattern.

- Reliability needs. If message delivery guarantees and retries are a top priority, fanout is the ideal choice compared to choreography.

- Team expertise. For teams with expertise in event-driven design and monitoring distributed systems, the choreography pattern would be best suited.

Examples of a hybrid approach

In the real world, systems often implement a combination of both. For example:

- Teams might use a message broker for very critical and high-volume events -- fanout -- while still allowing some services to react directly to events from others -- choreography.

- Teams might use a broker to handle just the initial event distribution, but the services then emit secondary events for downstream choreography.

Wisdom Ekpotu is a DevOps engineer and technical writer focused on building infrastructure with cloud-native technologies.