Detecting rogue mobile devices on your network

Controlling what mobile devices connect to your network is crucial, whether those devices are local or remote, stationary or mobile. Many enterprises use application portals, mail servers and/or VPN gateways to detect and restrict mobile access, complemented by IPS to spot anything that slips through the cracks. Such techniques can be effective, but today's mobile devices can present new challenges that deserve further attention. Lisa Phifer discusses the challenges being introduced by today's increasingly diverse mobile devices and discusses some emerging techniques to deal with them.

Detecting and restricting rogue mobile devices that connect to your network is the key to your network security. In this series, you'll learn about tools and techniques that can help you identify those pesky mobile devices that may be connecting to your network without your knowledge.

Auditing the airwaves

Guarding the gate

New challenges in mobile device discovery

| Auditing the airwaves by Lisa Phifer |

Controlling which mobile devices can connect to your network is crucial to ensuring the privacy and integrity of corporate assets and data. Despite this, virtually every network audit uncovers at least a few surprise nodes, ranging from printers and wireless APs to mobile devices carried by visitors, suppliers and employees.

To avoid the resulting embarrassment or penalty, institute a routine process for discovering all new devices that connect to your network without your knowledge. In this three-part series, we explore several readily available methods for mobile device discovery, starting with wireless transmission monitoring.

Something in the air

Many companies control on-site mobile access to the network in one of two places -- at the access point (AP) where wireless traffic is switched onto the LAN or at the captive portal or firewall where users are authenticated. These measures do a fine job of guarding the "front door" to your network -- the entrance through which everyone is expected to enter. But they ignore unguarded back doors where most security breaches tend to occur.

Specifically, many surprise devices are connected inside the wired network. From conference room APs installed by employees for convenience to laptops that bridge between a neighbor's WLAN and your Ethernet, poorly placed wireless devices can provide invisible-but-unfiltered outsider access to business systems. Even a short-range technology like Bluetooth can unwittingly expose sensitive data and permit unauthorized use of network connectivity services.

The first step toward closing any wireless back door is to find it. Clearly, you want to discover all previously unknown wireless devices that appear to be connected to your wired network. You also want to identify known devices that form unapproved wireless connections to external devices such as visitor handhelds or metro-area APs. In short, your goal is not simply to discover unknown wireless devices but to spot (and then stop) unauthorized and potentially risky wireless connections.

Periodic scanning

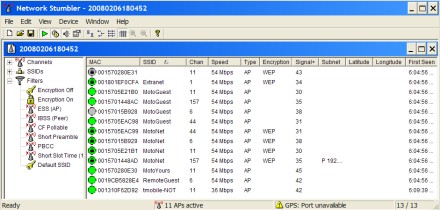

One popular method is to scan your office for wireless devices on a daily, weekly or monthly basis. In a small business or branch office, this can be accomplished by touring the facility with a portable wireless scanner -- often called a "stumbler" in honor of Marius Milner's original Wi-Fi NetStumbler (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scanning for Wi-Fi APs and Ad Hocs

Scanners like NetStumbler use 802.11 probes to find Access Points and Ad Hoc (peer-to-peer) nodes. Other scanners, such as Wellenreiter, listen passively for beacons. All you need is a laptop or PDA with scanner software and a compatible Wi-Fi card. Depending on card sensitivity, antenna, and RF obstacles, a Wi-Fi scanner can usually find active APs and Ad Hocs up to 300 feet away.

Most Wi-Fi scanners don't identify client devices that connect to APs, however. For that, you need a Wi-Fi protocol analyzer that captures and decodes everything it hears. For example, Wireshark is a popular open source protocol analyzer that can use a Wi-Fi card in monitor mode to capture 802.11 packets and then list all source and destination devices (i.e., Wi-Fi APs and their clients).

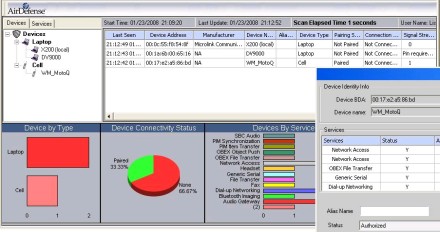

Wireless scanning is not limited to Wi-Fi. For example, Bluetooth scanners like the one illustrated in Figure 2 use 802.15.1 Peer and Service Discovery protocols to detect other devices and their supported services.

Figure 2. Scanning for nearby Bluetooth devices

A Bluetooth scanner can usually find any type of Bluetooth device -- from mobile phones and headsets to printers and APs. But you need to get much closer to each device, since the most common class of Bluetooth device reaches just 30 feet. Furthermore, you will only find Bluetooth devices that are configured to participate in discovery.

Continuous monitoring

If you periodically scan your office, you will probably find many wireless devices that belong to your company, your neighbors and your guests. You must maintain a list of known devices so that you can tell when a new one shows up. However, a "rogue" AP could be installed for weeks before you notice it. You will also miss the vast majority of transient mobile devices and risky connections that your own clients establish with unknown APs or Ad Hocs.

Alternatively, a Wireless Intrusion Prevention System (WIPS) provides continuous monitoring for known and unknown wireless devices. Not only is full-time monitoring less likely to miss devices, but it can alert you to potential threats within minutes.

A WIPS can usually compare each discovered device's address to a list of known/trusted devices. It may trace wired connectivity to determine whether a potential rogue AP is actually plugged into your network. A WIPS might even decide whether observed connections conform to your configured policies. This automated analysis can draw your attention to high-risk devices so that you can more efficiently ignore neighboring APs and visiting clients that never even try to connect to your network.

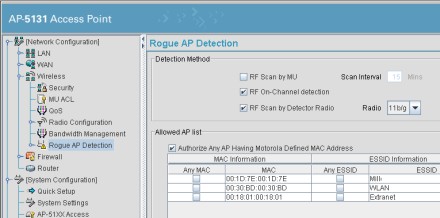

There are two approaches to continuous wireless monitoring: embedded WIPS and overlay WIPS. In the embedded approach (Figure 3), your APs monitor the air around them. Some just spend their spare time listening for unknown APs. Others can be configured to use one radio to handle traffic and a second radio to listen for APs. Some switches can even convert an ordinary AP into a full-time monitor, as needed.

Figure 3. Embedded rogue detection

In this case, rogue AP discovery is just one of many things that your WLAN does for you. An embedded WIPS will spot more devices, faster, than you could ever hope to spot with periodic scans. If you have a large distributed network, this approach will also be far less labor intensive than scans, but an embedded WIPS usually stops with discovery – it's up to you to investigate and remediate each new device.

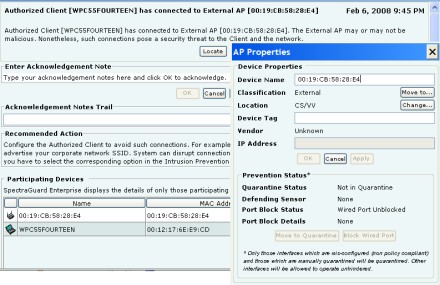

Or you could deploy an overlay WIPS that uses dedicated sensors instead of APs to monitor the airwaves. Those sensors, installed throughout your offices, report back to a dedicated WIPS server that automatically investigates and responds to detected threats. For example, most overlay WIPS can use a sensor near a rogue AP to break any connections that it might form with your own clients (Figure 4). A WIPS can also combine multiple sensor observations to approximate an AP or client's location so that unauthorized devices can be removed without extensive searching.

Figure 4. Overlay WIPS prevention

Conclusion

All of these discovery methods monitor wireless traffic to spot new unknown devices, but they vary greatly in terms of cost, simplicity, efficiency and effectiveness. Many small businesses rely exclusively on periodic scanning, while most large enterprises invest in embedded or overlay WIPS for more comprehensive, efficient discovery. In fact, the line between embedded and overlay WIPS has become blurred by OEM partnerships between WLAN infrastructure and security vendors. Ultimately, the best approach for your business will depend on the size of the area to be monitored, the security policy you need to enforce, and your level of risk tolerance.

Of course, watching the airwaves is only one way to discover unknown devices. In the next section, we'll explore other methods that use your wired network to detect off-site and non-wireless devices that just might be connecting without your permission.

| Guarding the gate by Lisa Phifer |

In the last section, I wrote about the importance of detecting what is really connecting to your network, starting with techniques for discovering on-site wireless devices. But short-range RF monitoring cannot detect mobile devices that access your servers and data from afar. At a recent Gartner Mobile Wireless Summit, we explored this topic with vendors and analysts.

Getting in sync

For many mobile devices, periodic data synchronization with an enterprise server or desktop is a primary point of corporate contact. A decade ago, Palm Pilots started using cradles to synchronize directly with desktop PCs. Today, mobile workers are more likely to synchronize handheld devices "over the air" with DMZ (demilitarized zone) email servers like Microsoft Exchange or mobile device managers like Sybase iAnywhere Afaria.

"When any mobile device synchronizes with a desktop using Bluetooth or a cradle, if an Afaria client is running on the desktop, it can block that sync activity," said Joe Owen, vice president of engineering for Sybase iAnywhere. "Alternatively, a message may be returned to the desktop with instructions to install Afaria on new mobile devices."

But, according to Owen, desktop synchronization has become old-school. "Most of our customers are now locking down desktops to stop [mobile devices] from coming in that way," he said. "They prefer to deal with mobile devices at the perimeter or on the DMZ, using some type of gateway."

In fact, Gartner's John Girard strongly recommends disabling cable and cradle-based synchronization. "The moment that I open up desktop synchronization, I have a secondary path that's hard to monitor and control. If I don't have an agent on that [desktop], then I'll never even know it happened," he explained.

Instead, Girard recommends that devices be "checked at the gate" when they first attempt to enter the company network to reach office systems and servers. "Even if users control their own [mobile] devices, the company does not need to give up control to its central and office facilities. Access controls at the boundaries of WAN, LAN and server take on increasingly important roles to prevent damage from improper usage."

Perimeter detection and provisioning

For example, Afaria customers can detect unauthorized or unprovisioned Windows Mobile devices when they attempt to synchronize with Microsoft Exchange. "We offer software that can be run on the Exchange Server as an ISAPI add-in to detect synchronization attempts," Owen said.

All correctly provisioned devices are permitted to sync with Exchange, while the rest receive error messages containing a URL for over-the-air provisioning. Alternatively, an SMS message could be sent to newly issued mobile devices, containing the provisioning URL. Mobile users follow the URL to a corporate Web server, where they are presented with a confirmation message to download and install the Afaria client.

The appropriate client package, including Afaria software and policy, is then pushed to the device -- typically over a wireless WAN, but potentially over any Internet connection. Once the client has been installed, the mobile device automatically connects to an Afaria server on the corporate DMZ at scheduled intervals. That server checks each mobile device's ID against administrator-configured blacklists and whitelists to enforce policies on authorized devices and wipe lost or stolen devices. Connection attempts and inventoried attributes are logged for use in reporting.

I experienced the user side of this process at the Gartner Summit by participating in a GO! Mobile Device Trial offered by Sybase and HTC. When I picked up my HTC Touch Dual, the client package had been installed but not fully provisioned. The latter was completed within a few minutes by connecting over wireless broadband to a remote Afaria trial server to download applications, content and settings, including iAnywhere Mobile IM and OneBridge email. However, initial device detection via Exchange synchronization was not part of this trial.

Beyond email

This one example illustrates how perimeter application servers can play a vital role in mobile device detection. Many mobile device managers now offer some degree of mail gateway integration, reflecting the dominance of email as a mobile business application. However, detection at other application portals and remote access VPN gateways will no doubt grow as mobile applications and their business usage expand. The final section will conclude with a look at new challenges being introduced by today's increasingly diverse mobile devices, and emerging techniques to deal with them.

| New challenges in mobile device discovery by Lisa Phifer |

Controlling what devices connect to your network is crucial, whether those devices are local or remote, stationary or mobile. Many enterprises use application portals, mail servers and/or VPN gateways to restrict mobile access, complemented by IPS to spot anything that slips through the cracks. Such techniques can be effective, but today's mobile devices can present new challenges that deserve further attention.

Look for leaks

At the Mobile Wireless Summit, we asked Gartner Distinguished Analyst John Girard for his advice on discovering mobile devices -- especially PDAs and smartphones that access and carry business data without corporate approval.

As a first step, Girard recommended scanning all desktop and mobile computers to detect unauthorized synchronization software and past sync activity. "If you are running SMS or LANDesk or something similar, you can easily take this kind of desktop inventory," he said.

But don't stop there. Some users may be forwarding corporate email to their own mobile devices. "With personal BlackBerrys and Windows Mobile smartphones, I can easily set up email to an outside ISP," Girard said. "Unless my company has a methodology to detect this, how would my company even know?"

To close this loophole, Girard recommended examining corporate servers and desktops for tip-offs like email or calls being routed to unusual destinations. "If your company is using a software distribution and inventory management system, you should be able to detect when these settings are out of compliance," he said. "Is there an application that's not supposed to be there or a configuration that's incorrect? Put procedures in place to stop [these policy violations], with help desk support to explain why they are blocked."

Expand edge security

During his summit session entitled "Mobile Security on a Budget," Girard recommended that employers leverage the network edge systems they already control to mitigate the risks posed by new mobile devices.

"As the intelligence of mobile phones increases, attack paths [like] over-the-air software updates and simple scripting attacks will be prevalent -- all of which flow through servers to distribute content," Girard said. "Enterprises should focus malicious-content protection investments on sync servers, wireless application gateways, and external wireless network service provider offerings through 2009."

To reduce risk, use these network edge servers and gateways to filter all mobile device network access, avoiding policies that permit split tunneling. "The best way to [reduce mobile device risk] is to put all of your applications back on servers," Girard said. "If you can't make a device secure, get all the local data off of it."

Smaller companies without security infrastructure can still implement this approach by procuring communication services that are inherently secure. "Buy device encryption and management from your carrier," he said, "and insist that their mobile communication service filters for malware."

Deal with unmanaged devices

User-owned devices now exist even within the most conservative, risk-averse companies, according to Girard. Ignoring reality will not help. Rather, enterprises must begin to assess and tackle this exposure.

Many IT managers already worry about personal PDAs and smartphones, but Gartner finds that employees have started to use personal laptops as well. "If you haven't done a survey to find out who's gone off the corporate [laptop] image recently, it's time," he said. "Even kids know how to roll back to a restore point created before [corporate security] was installed so that they can run social games that also happen to be great venues for malware."

To permit application access by user-owned devices -- and other unmanaged devices, such as home PCs -- companies can turn to "clientless" SSL VPNs. Where clientless solutions are too limited, SSL VPN "thin clients" can be used to deliver broader application access -- preferably after scanning the user's device. Both techniques are now being incorporated into network access control (NAC) solutions that combine user authentication with endpoint identity and health to determine the appropriate degree of access.

Girard warns, however, that it can be tough to differentiate between a known, trusted device and another device that intentionally mimics it. "It can be very hard to detect cloning of a legitimate device," he said. "But you can try by examining registry keys and looking at NIC addresses or other hardware attributes.

Go virtual

Finally, some SSL VPNs can create a secure virtual environment on the unmanaged device -- essentially an encrypted container in which to run trusted applications and use corporate data.

This is a step in the right direction, Girard said. But the best way for employers to manage risk on user-owned devices may be to deploy corporate-managed "virtual PCs." For example, products from VMware or Moka5 can be used to create standard corporate desktop environments on personal laptops (but not on PDAs or smartphones).

Virtualization could give IT departments far more control over the computing environment used for business activities, while reducing the impact on mobile devices when they are used for personal activities. In short, secure virtual environments can let employees work remotely, independent of the mobile device they happen to be using to reach the corporate network.

Note that, in this scenario, mobile device discovery becomes far less important -- at least insofar as hardware is concerned. But employers will still need to reliably detect and identify each mobile user's execution environment in order to ensure that it remains healthy and compliant with corporate security policies. After all, the wrapping paper may or may not be pretty -- it's what's on the inside that really counts.

About the author: Lisa Phifer is vice president of Core Competence Inc., a consulting firm specializing in network security and management technology. Phifer has been involved in the design, implementation, and evaluation of data communications, internetworking, security, and network management products for nearly 20 years. She teaches about wireless LANs and virtual private networking at industry conferences and has written extensively about network infrastructure and security technologies for numerous publications. She is also a site expert to SearchMobileComputing.com and SearchNetworking.com.