Will 2026 be the year deepfakes go mainstream?

Deepfakes are now so easy to create that anyone with a browser can make one. With cheap tools and abundant data, 2026 could be the year they go from novelty to mainstream threat.

Recently, an article in The Guardian talked about the industrialization of deepfake campaigns. We've all seen the news about high-profile deepfakes and seen how convincing (or not) they can be, but I hadn't heard the term "industrialization" yet. So, I set out to write a blog post about how easy it is to make them, showing how to do it, the tools that bad actors use, etc.

The problem is that it's so ridiculously easy to make a deepfake that there's nothing to write about. You can go to ElevenLabs right now, upload a photo -- not even a video -- of yourself and record 30 seconds of audio, and it will generate a video of you saying whatever you type. That's it. I could make a video of myself saying "Go Michigan!" right now, and I assure you, that is not something this Buckeyes fan would ever say voluntarily.

No command line. No model training. No technical skill whatsoever.

And ElevenLabs is just the one I happened to use. There are many more, including the following:

- HeyGen, which focuses on creating videos in the same way using AI avatars.

- Descript's Overdub, which lets you clone a voice into a video and edit what it says like a text document.

- JoggAI, which advertises itself as a tool to "make deepfake videos ethically and safely."

- DeepFaceLive, a real-time face-swapping tool.

- FaceFusion, which lets users tweak faces. So, for example, you could use it to make a 10-year-old headshot on LinkedIn look older, then overlay it on a video of someone else.

Some are paid or free online services, while others are open source projects on GitHub that anyone can download and run locally with no guardrails at all. The point is that there are dozens of these tools, they're getting better by the month and the baseline skill required to use them is basically just access to a web browser.

To be clear, most of these tools aren't made for the sole purpose of creating malicious deepfakes (though I have to say, JoggAI is the first I've seen use the term "ethical" to describe their deepfakes). The issue, ultimately, is one of intent. This thing exists, and it can be used for good or evil. In that way, you could say the same about email. Or the internet. Or bananas. So, I'm not judging any of these tools.

That's how my how-to post died on the vine. You can't write a compelling walk-through when every tool is a three-step process. Then I realized: That is the story!

Source material for deepfakes is everywhere

The ease of creating a deepfake is only half the equation. The other half is the raw material, and it's everywhere. Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, LinkedIn -- each contains an element of your voice, mannerisms, images and the way you dress. There's more than enough publicly available audio and video to clone a convincing likeness, and that's not even counting things that can make deepfakes more convincing, like your favorite sports teams, the college you attended and more. This data is out there about practically everyone, and there are bots out there scraping everything they can.

Now pair that with an AI agent -- not a person -- that's been tasked with targeting a single individual. The agent doesn't get tired. It doesn't lose focus. It can scour social media or scraped databases for personal details, craft a scenario tailored to the target, generate the deepfake and deliver it through the right channel at the right time. If that fails, it can adjust the approach to a new vector, new fake person, new audio, etc., and try again. A scammer just needs to point the agent at someone and wait.

This is the industrialization of deepfakes. It's not that deepfakes exist; we've known that. It's that the barrier to creating and deploying them at scale has essentially disappeared.

Research data backs up the deepfake concerns

I found data backing up these concerns in my Omdia study, "The Growing Role of AI in Endpoint Management and Security Convergence." The research shows that 41% of organizations report that AI is increasing the quantity and sophistication of phishing and social engineering attacks. That's not a projection; that's what they're seeing today. Just 1% said AI-driven attacks hadn't affected them.

Deepfakes specifically are showing up in the data as an emerging concern. In another recent Omdia report, "The Email and Messaging Security Imperative," 30% of respondents identified advanced threats delivered through messaging -- including deepfakes, business email compromise and AI-generated content -- as a challenge with their collaboration platforms. Perhaps most concerning, though, is that 72% of organizations face socially-engineered attacks across multiple communication channels on at least a monthly basis. The multi-vector, multi-channel social engineering attack is already the norm, and deepfakes are the newest weapon in that arsenal.

Why deepfakes will be harder to defend against than phishing

Deepfakes could very well be a harder problem to solve than phishing. While 38% of respondents said phishing or spear phishing had penetrated their security controls, and phishing is becoming increasingly sophisticated due to AI, we've had 15-plus years of practice with it. We've trained users, built filters and developed playbooks. We know what to look for because we've been looking for it since the days of Nigerian prince emails.

Deepfakes are different. With phishing, we taught users to check the sender, hover over links and look for urgency cues. There's a pattern to recognize. While some of this applies to deepfake videos or audio clips, users need to know the person well enough to spot that their voice sounds slightly off, or that they'd never use that particular phrase. If it's your direct manager, maybe you'd catch it. If it's your CEO, or a vendor you've met twice, or a new executive you've only seen on a company-wide Zoom call, that's a different story.

It's easy to dismiss voice cloning if you only try it on yourself. When you record your own voice on ElevenLabs and then ask it to generate speech, you immediately hear the flaws. You'd never say that word with that inflection, or the cadence is off, or a word is slurred. But that's because you know your own voice better than anyone. For someone who doesn't? It can be convincing enough.

So what do we do about deepfakes?

Deepfake detection technology is emerging, but it's in the same position that every defensive security technology occupies: perpetually one step behind the attackers. It's the same cat-and-mouse game we've always played with malware and endpoint detection and response. We assume the threat is coming and try to spot the anomalies.

The one piece of good news is that deepfakes have a narrower delivery surface than phishing. Phishing hits you through email, messaging apps, SMS, social media -- basically anywhere text can travel. Deepfake audio and video are more constrained. They show up in voice calls, video calls, maybe a well-crafted voicemail. (Sure, someone could text you a deepfake video, but that's a red flag since nobody communicates that way.)

That narrower scope means there might be an opportunity to teach users specific behaviors for specific channels -- verifying unusual requests through a different medium, establishing code words for financial approvals, and treating any unexpected video or audio message with the same skepticism we've learned to apply to email.

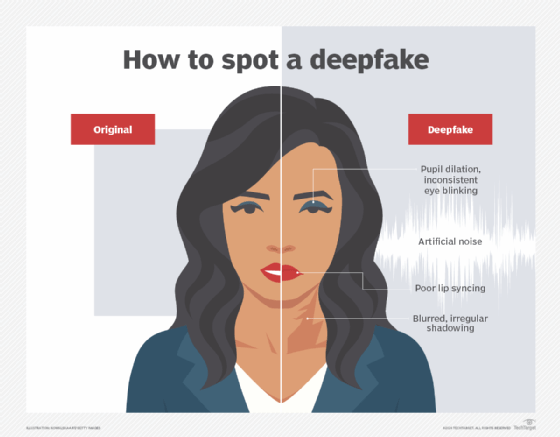

But let's be realistic. This is a new pattern, and even the savviest users haven't seen enough deepfakes to recognize a pattern yet. Also, while there are guides out there highlighting ways to detect deepfakes, scammers see these, too. Just like phishing email text, as time goes by, audio and video will also get better.

The defense is coming, though

That said, there are signs that the industry is starting to take this seriously as more than a future problem. The following developments are promising:

- Both Intel and AMD are partnering with security vendors to run deepfake detection models directly on the neural processing unit in AI PCs. Most seem to be consumer-facing, but it's not hard to imagine EDR or platforms adding this to their portfolios.

- Email security vendor Ironscales has focused on deepfake detection capabilities for a few years, including live analysis of audio and video that looks for synthesis artifacts. I'm sure other email security vendors will follow, especially as deepfakes increasingly get delivered alongside or in support of traditional phishing and business email compromise campaigns.

- Companies like Netarx are developing tools specifically aimed at deepfake detection across communications channels.

- Training and education companies like KnowBe4 are building deepfake training programs to support end-user awareness.

There's so much activity in this space, and I'm thinking 2026 might be the year deepfakes move from a few high-profile cases used to generate fear, uncertainty and doubt to a mainstream problem -- not as a hypothetical conference demo, but as a real and recurring component of social engineering campaigns.

Not convinced? Try it yourself over lunch and see just how easy it is.

Gabe Knuth is the principal analyst covering end-user computing for Omdia.

Omdia is a division of Informa TechTarget. Its analysts have business relationships with technology vendors.