Review 6 phases of incident response for GCIH exam prep

'GCIH GIAC Certified Incident Handler All-in-One Exam Guide' takes a deep dive into the six phases of incident response to help security pros with GCIH exam prep and certification.

To be a successful incident handler, you need to know exactly what to do, when to do it and why.

"Incident responders are considered the elite of the cyber world," said author and incident response veteran Nick Mitropoulos in his book, GCIH GIAC Certified Incident Handler All-in-One Exam Guide, published by McGraw Hill.

The book is designed to help candidates pass the Global Information Assurance Certification (GIAC) Certified Incident Handler (GCIH) exam but can also function as a reference for anyone looking to sharpen their incident response techniques. Readers are instructed how to create a test lab where they can practice the incident response methods and principles discussed throughout the book. This step is essential for those candidates with less professional experience who will require more preparation for the hands-on aspects of the GCIH exam.

In the following excerpt from Chapter 2 of GCIH GIAC Certified Incident Handler All-in-One Exam Guide, Mitropoulos, global security operations and engineering manager at professional services firm Alvarez & Marsal, details the preparation phase of six incident response levels.

After reading Chapter 2, take the practice GCIH exam questions to see what you have learned.

Be sure to check out a Q&A with Mitropoulos, who offers insights on the certification. Also, download a PDF of Chapter 2 to read the entire chapter, which includes additional GCIH exam questions on the six incident response phases.

Incident Handling Phases

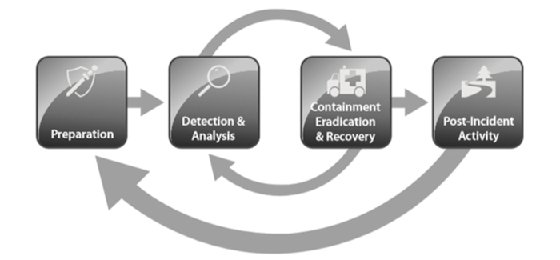

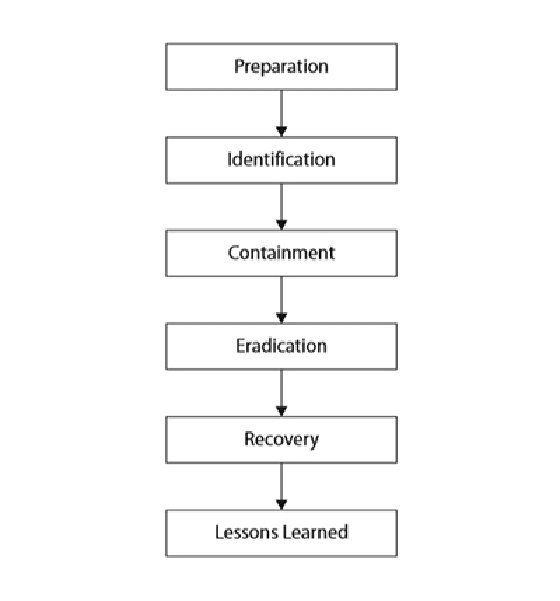

A mapping of the NIST framework for the purposes of the exam can be seen in Figure 2-2.

As you can see, the Containment, Eradication, & Recovery phase has been split into three separate phases. That can help your organization explicitly state what activities need to be performed during each phase.

Click to learn more about

Click to learn more about

GCIH GIAC Certified

Incident Handler

All-in-One Exam Guide

by Nick Mitropoulos.

Any incident you experience can be analyzed by following the phases that were mentioned in Figure 2-2. Note that preparation refers to all the activities you need to take prior to an attack. For example, if you anticipate SQL injection attacks against one of your web servers, you might decide to install a web application firewall (WAF) during the preparation phase to prevent such attacks. Identification occurs when you declare an incident, like when a security analyst identifies a data breach where information is being exfiltrated from your organization and is destined to an external IP address that the attacker controls. After the incident is identified, containment follows. A possible containment step in this example might be to block communication to that external IP address at your perimeter or isolate the originating device from your network so further data transfer doesn't take place. Moving on to eradication might lead you to identify a rootkit that the attacker had installed on the compromised system, which you will need to remove. Following that, recovery might entail building up a fresh copy of the affected system from a previously taken backup. Finally, a lessons learned session can be conducted to report upon all the incident findings and identify gaps for future improvement.

CAUTION

As a rule of thumb, it is recommended to fully complete a phase before moving on to subsequent ones. That will help ensure the incident has been handled fully, without missing or overlapping steps. However, you still need to allow for some degree of flexibility. For example, new evidence might be identified that will require you to go back to a previous phase and repeat certain actions.

Preparation

As the name implies, all of the activities discussed here are actions you need to perform well before an incident takes place. They are necessary for you to be able to effectively respond to any attack. Also, consider the possibility that an attacker is already present in your network without your knowledge. Performing the tasks discussed later may prove crucial to identifying an ongoing or recent attack and make the difference between successful identification and subsequent eradication of that threat versus not even being aware of it. Preparation includes the following:

- Building a team

- Getting information about the organizational network and its critical assets

- Creating processes

- Obtaining the required hardware and software

Building a Team

Building a team may arguably be classified as the hardest part of the preparation phase. It is also usually the most time consuming. Depending on the team's target size, this process may take anything from a few weeks to several months, especially if you are trying to build a large-scale team spanning across different geographical locations. Other challenging considerations that need to be addressed are the team's remit, working model, mission objectives, available budget, ideal size, requirements for outsourcing any elements to third parties, and a lot more.

Required Skills

Incident responders are considered the elite of the cyber world. They are the equivalent of special forces teams in the army. As such, they are required to possess a variety of skills to be effective in their roles and able to tackle any security incident that comes their way. The range of desired skills heavily depends on the needs of your company as well as the team's objectives, but at a minimum, they need to possess the ability to perform the following tasks:

- Log review. They need to be comfortable analyzing a variety of logs like IDS, IPS, firewall, antivirus (AV), proxy, Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP), Active Directory (AD), DNS, endpoint, application, and system logs.

- Detection rule creation. An ability to create detection rules is required so that any indicators of compromise (IOCs) that are extracted during an investigation can be used to create detection rules to identify that activity in the future.

- Network forensics. This is a key element of incident handling because network traffic analysis can aid greatly in identifying what activity has taken place. Incident handlers need to be comfortable analyzing packet captures taken from a variety of devices (like endpoints and servers), extracting data of interest, and creating a timeline of activities that took place on the network.

- Endpoint forensics. Performing endpoint forensics can be quite challenging due to the variety of operating systems and types of devices. As such, incident responders need to be comfortable performing endpoint forensics on desktops, laptops, servers, and phones. In addition, they need to be comfortable with all major operating systems like Windows, Linux/Unix, macOS, iOS, Android, Windows Mobile, and BlackBerry (including any older OS versions, since those may be encountered at any client environment).

- Malware analysis. Whenever an investigation leads to a suspicious file or process, an incident handler needs to be able to analyse the item in question and ascertain if it's malicious or not. If it is, then the investigator will use a series of techniques, like sandbox/static/dynamic analysis, to identify what specific actions the malware is trying to perform and will use that knowledge to build detection capability that will protect the organization.

- Scripting. Being able to automate various activities using a scripting language is quite useful, as it drastically reduces response times when obtaining required information. It also allows the incident handler to perform other tasks while scripts are running in the background.

Operational Model

The selection of a suitable model depends heavily on the organizational requirements. Common considerations that drive decisions often relate to:

- Mission objectives. What are they key aspects of any incident the team is expected to address? Is it just identifying a potential intrusion, providing mitigation, and then handing over the incident to another team for further investigation? Is the team expected to reverse-engineer any malware samples, or is that going to be handed off to an AV vendor or other third party? Is forensics a part of the daily tasks? Is the team going to be dealing with external and insider threats?

- Need for extended hours availability and distributed teams. Some companies, like banks or critical public-sector entities, require personnel to be present in an operations room at all times (also referred to as 24 × 7 or 24 × 7 × 365 support). Others choose to have personnel on-site during core hours (for example 9:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m.) and then someone is on call to provide after-hours support. Some companies use geographically distributed teams that are located in different time zones over a follow-the-sun model (each team works 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. at their location and then hands over to another team, which also works the same core hours at another location, thus supporting the organization around the clock).

- Budget. Cost can be a heavy limiting factor when building up an incident response team. When you want to hire the best of the best, it tends to cost a lot. As such, decisions need to be made regarding what key individuals to hire or what functions might need to be supported further down the line. If there's any need for after-hours work, that will also come into play, as it tends to be quite expensive (for example, having the team working on call, overtime, or during night shifts).

Three main models are used, which heavily depend on the degree of outsourcing you intend to put in place:

- Full-time response team. This type is often used in environments where a large volume of incidents is anticipated and a team is required to operate at all times to be able to support all investigative activities. In addition, very sensitive environments (like military or governmental departments) have their own teams so there's no possibility for information leakage by a third party during an incident.

- Partially outsourced response team (also known as functional response team). Some of the organizational activities are being outsourced to a third party. For example, an external company might be hired to review device alerts and perform level 1 analysis. Once something interesting is identified, it can be escalated to the company's internal team for further analysis. Other options include outsourcing specific tasks to an external party. Examples include the need for threat intelligence capability, after-hours monitoring, performing forensic investigations, and malware analysis. The advantage is that the organization can have a small in-house team with more limited technical skills and choose to outsource anything they desire to an external team. However, cost quickly becomes a consideration, as outsourcing tends to be quite expensive.

- Fully outsourced response team. All incident response activities are performed by an external company. The organization may choose this option when it doesn't have enough technically skilled employees to perform the type of required activities. In addition, it alleviates the responsibility and transfers all the risk to the external party, as they are solely responsible for all aspects of incident handling.

Practice GCIH exam questions

These questions from Chapter 2 of GCIH GIAC Certified Incident Handler All-in-One Exam Guide are designed to test your knowledge on the six phases of incident response.

About the author

Nick Mitropoulos

Nick Mitropoulos

Nick Mitropoulos is the global security operations and engineering manager at Alvarez & Marsal. He has more than 14 years of experience in security training, cybersecurity, incident handling, vulnerability management, security operations, threat intelligence and data loss prevention. He has worked for a variety of organizations, including the Greek Ministry of Education, AT&T, F5 Networks, JPMorgan Chase, KPMG and Deloitte and has provided critical advice to many clients regarding various aspects of their security. He is SC/NATO security cleared, a certified (ISC)² and EC-Council instructor, a Cisco champion and a senior IEEE member, as well as a GIAC advisory board member. He has an MSc, with distinction, in advanced security and digital forensics from Edinburgh Napier University. He holds more than 25 security certifications, including GCIH, GPEN, GWAPT, GISF, Security+, SSCP, CBE, CMO, CCNA Cyber Ops, CCNA Security, CCNA Routing & Switching, CCDA, CEH, CEI, Palo Alto ACE, Qualys Certified Specialist in AssetView and ThreatPROTECT, Cloud Agent, PCI Compliance, Policy Compliance, Vulnerability Management, Web Application Scanning and Splunk Certified User.

https://www.mhprofessional.com/9781260461626-usa-gcih-giac-certified-incident-handler-all-in-one-exam-guide-group