zephyr_p - stock.adobe.com

Ransomware negotiations: An inside look at the process

Ransomware negotiators are brought in to communicate with cybercriminals and hopefully arrange less expensive payments. How often do they succeed?

As ransomware attacks continue to surge across the globe, the demand for negotiation services has also increased -- and been hard to fill.

Kurtis Minder, CEO of GroupSense, experienced the rise firsthand over the last year. GroupSense, a threat intelligence vendor based in Arlington, Va., specializes in reconnaissance for post-attack engagements to gather information about emerging threats.

Minder said a significant number of the company's customer wins are incident response-driven; often, he said, larger incident response vendors would bring GroupSense into breach scenarios to provide additional analysis of specific threats in the wild. But something began to shift in the incident response business, starting in early 2020.

"What happened was we got pulled into a very large incident -- it was a Nasdaq-traded company that suffered a very large breach," he said. "We had detected the threat and alerted them, and they brought in their own incident response firm and then brought us back in after the fact."

Cyber insurance carriers typically have lists or "panels" of approved vendors for various incident response services that address breaches and ransomware attacks, including ransomware negotiations. In this case, according to Minder, the victim had just one company for ransomware negotiations on its panel, and that company was "completely overwhelmed" with demand at the time. As a result, GroupSense stepped in and conducted the negotiations with the threat actors, which opened the door for future engagements with that carrier.

Soon, the company took on other negotiation jobs. As a result, GroupSense launched dedicated services for ransomware negotiations last September. Minder said he was conducting three to five negotiations a week after the launch.

Not too long ago, ransomware negotiations were viewed by many as a largely unscrupulous endeavor performed by shady ransomware recovery firms that would claim to decrypt victims' data when in fact they were covertly paying the ransoms behind the scenes.

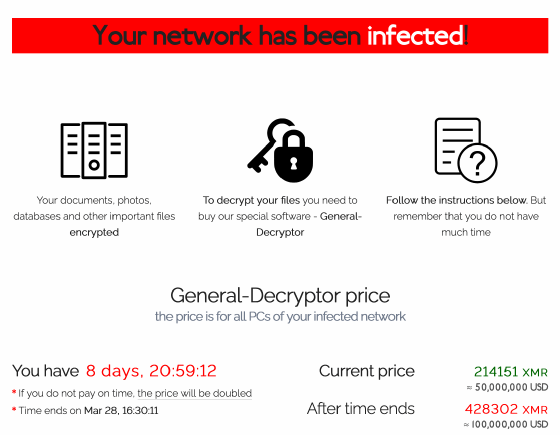

But times have changed. Ransomware attacks have steadily increased, as have the ransom demands, which infosec experts say routinely reach seven figures. Experts also say many victims, even those with proper backups to restore encrypted data, are now opting to pay ransoms to prevent any exposure of stolen data.

Those factors have driven up demand for incident response specialists who can delay a pressing payment deadline and negotiate a million-dollar demand down to $200,000. Here's how they do it.

The negotiators

Karen Sprenger is COO of LMG Security, an infosec consultancy based in Missoula, Mont., but her unofficial title is "chief ransomware negotiator." She fell into this role about three years ago when ransomware incidents became increasingly common. At that time, negotiating with ransomware threat actors wasn't nearly as common as it is today.

"I've started to see more clients request ransomware negotiations, and I think part of the reason for that is we're seeing more of the data extortion component," Sprenger said. "Before, customers could say 'I've got backups; I don't need to pay because I can restore my data.'"

But that has changed now with data theft and exposure tactics, which Sprenger said have led to an increase in negotiations for LMG.

Kevin Kline, COO of infosec consultancy Aggeris Group in Essex, Conn., has also seen a steep rise in ransomware attacks, hefty ransom demands and more victims who are willing to pay. Before joining Aggeris Group in 2019, Kline spent nearly 30 years with the FBI, most recently serving as assistant special agent in charge of the New Haven, Conn., field office.

Kline said it's hard to determine the full scope of ransomware attacks today. Earlier this month, the FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) annual report showed a significant increase in ransomware incidents in 2020, as well as financial losses -- 2,474 complaints reported to IC3 and losses of more than $29 million, compared with 2,047 complaints and just $9 million in losses the year prior.

The IC3 routinely discloses that its ransomware data is "artificially low" for a variety of reasons. But like other infosec professionals, Kline said he believes the IC3 report numbers are extremely low and don't provide an accurate picture of the problem.

"In a number of instances, companies that are subject to ransomware attacks do not want to report the matter for a number of reasons: Preventing the public from knowing and undermining confidence in their brand or stock, the ability to handle themselves with support from another company and the inclusion of an NDA, or the fear of having a government entity inside of their network and systems all lead to companies underreporting both the attacks and the amount of loss," Kline said.

Rather than report attacks to law enforcement, which typically don't have the time or qualified personnel to resolve incidents within short windows and tight deadlines, businesses often outsource at least part of the remediation effort to incident response firms like Aggeris Group to quickly -- and discreetly -- address the problem in an expedited manner. And in many of these cases, Kline said, clients opt to pay the ransoms.

Like Sprenger, Kline said he believes the data thefts and exposure threats have led to a rise in payments. But paying isn't necessarily the right strategy, since you're left to trust cybercriminals to destroy the stolen data.

"It's more about the appearance of showing that you did everything you could to protect customer data," Sprenger said.

Another contributor to the rising number of paid ransoms is cyber insurance; more enterprises have policies that will cover the price of most ransoms, and the threat actors know it. "There seems to be an understanding [from attackers] that a lot of companies have cyber insurance and that the policies will pay for the ransom," Kline said.

These trends have put negotiations services in higher demand, but Minder said it's not an easy business. For one, negotiation services don't generate a lot of revenue. When GroupSense was building its offering, there were suggestions that compensation for negotiation services be a percentage of the paid ransom.

"The problem with that is it ripe for fraud between me and the bad guys," Minder said, adding that GroupSense instead charges an hourly rate as part of its incident response services.

Another challenge for negotiators is that threat actors can simply "go nuclear," as Minder said, by doubling an already-high ransom demand or exposing stolen data on the internet.

For example, threat actors who attacked Acer with REvil ransomware last week broke off talks with a negotiator working on behalf of the computer maker and refused to lower their demand of $50 million. The threat actors later threatened to launch DDoS attacks against the company, claiming such attacks would continue for years.

"If a threat actor decides to go nuclear during a negotiation, then that may reflect poorly on us," Minder said.

Let's make a deal

Ransomware negotiations can vary from incident to incident, but there are some commonalities. For example, all three negotiators say threat actors are usually willing to at least discuss lowering their demands.

For GroupSense, 100% of the negotiations so far have resulted in lower payments, Minder said. Ransom demands often start out at "exorbitant" prices, he said, but they can be negotiated down to more reasonable levels or reduced by at least 10%.

LMG had a recent case where attackers initially demanded $800,000. When Sprenger simply asked if the attackers were open to negotiating, the ransom was immediately dropped to $600,000. "I didn't even have to name a price at that point," she said.

Before negotiations start, the incident response firms must first discuss the incidents with their clients. What starts as a technical discussion about the specifics of the attack then becomes a business discussion about whether to pay.

"Incident response starts with the 1s and 0s and the type of encryption the ransomware is using," Kline said. "If the client is truly locked out of their systems, then we go to the client and ask what it means to them in terms of lost access, downtime and reputation."

Sprenger said there are occasional cases where victims that have proper backups in place choose to pay the ransoms -- even when no data has been stolen -- because they believe it's the fastest way to recover from the attack (LMG does not recommend that approach). But typically, the decision to pay or not is largely based on whether systems can be restored from backups and if confidential data has been stolen.

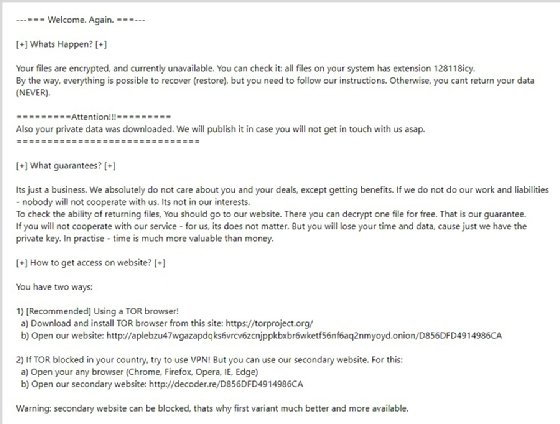

Once the decision to pay a ransom has been made by the client, the negotiators contact the threat actors. Previously, ransomware gangs used email, but most of the well-known, successful groups now have "customer service" portals for live chats.

Establishing trust with the threat actors is key, Minder said, and part of that is being upfront about who you are and what you're doing. "We never tell the threat actors who we are, but we tell them we are a third party negotiating on behalf of the customer."

The negotiators, meanwhile, must assess the threat actors and ask some key questions. Does this ransomware group have a history of decrypting systems after payment, or is its track record spotty? Is the threat actor an operator of this ransomware group, or a random affiliate that purchased the ransomware code on a dark web market? Has the group exposed victims' data even after they've received ransom payments?

And while ransom demands can vary wildly from victim to victim and gang to gang, Kline said these days, the numbers tend to be very large and sometimes based on the victim's brand or type of industry. "The bad guys always go high for ransoms now," he said. "They'll know generally what industry a company is in, like healthcare, but maybe not the specifics like how much cash on hand they have."

Sprenger said in some cases, LMG has found certain ransomware groups scanning victims' files for balance sheets and cyber insurance information. In one case, the threat actors gained access to the victim's cyber insurance policy and knew that the maximum ransom payment the policy would cover was $2 million; as a result, the threat actors settled for a $1.95 million payment.

As with almost all ransomware negotiations, time is critical. Victims are often given deadlines -- sometimes as long as a week, sometimes as little as 24 hours -- to respond and/or pay ransoms. And often, ransom notes drop on what LMG calls "Forensic Fridays" because, as threat researchers have noted, attackers like to strike on or just before the weekend.

While the ticking clocks can add pressure for victims and negotiators, Kline said it can sometimes be used to their advantage.

"If we get a big ransom demand, $1 million or more, and we counter with 'We can pay you $100,000 in an hour,' they usually take it," he said. "Taking a quick cash payment is more attractive to them than negotiating for days or even weeks and waiting for cyber insurance payments for $250,000 or $500,000 demands that they ultimately may not get."

Obstacles and questions

Negotiations can sometimes turn tense, especially when threat actors are unwilling to negotiate or asked to provide substantial evidence they've actually stolen a significant amount of sensitive data. Minder said negotiators have to get a feel for the threat actor and an accurate read on the tone of the conversation, which can be difficult.

"It's a soft skill," he said of negotiations. "It's not easily taught."

There are also potential language barriers. Kline said most of Aggeris Group's negotiations are with threat actors who appear to be non-native English speakers, based on email exchanges and chat conversations. And most attackers are willing to negotiate a lower payment, though occasionally they'll terminate communications and move on to other victims.

The negotiators said nearly all threat actors follow through with decryption upon payment, though Sprenger said LMG has sometimes run into cases where the encryption used by specific ransomware variants has trouble with SQL databases, for example. And occasionally, the decryptors will contain hidden backdoors and other malware.

But even though the majority of attackers provide decryptors, a nagging question remains for negotiators: Do the threat actors actually destroy victims' data? Sprenger said she's seen no indication that any of the attackers she's dealt with have gone back on their promises and sold or exposed victims' data after a payment. But she's not convinced it hasn't happened.

"I think it's a little too soon to tell," Sprenger said. "It's a money-making opportunity, so I wouldn't be surprised if they sold the data."

Sprenger cites Uber's notorious breach in 2016, which was covered up by several executives, as evidence that hackers can't be completely trusted. Last August, the Department of Justice announced former Uber CSO Joe Sullivan had been indicted on two criminal counts in connection with the attempted cover-up of the breach.

Sullivan and others were accused of paying $100,000, disguised as a bug bounty payment, to two individuals who obtained Uber's corporate data from an Amazon S3 bucket. The two individuals, who pled guilty to extortion for the hack in 2019, agreed to delete the stolen data in exchange for the payment; however, they didn't inform Uber that a third, unnamed individual was also involved in the breach and had apparently kept their own copies of Uber's data.

At the end of the day, Minder said, it's up to the client to make the final decision. Some GroupSense clients are large enterprises that have a CISO as well as outside counsel, breach coaches, incident response vendors and cyber insurance representatives all sitting at the table and providing feedback, while other clients are small and midsize businesses like a regional dairy farm that has a single IT operations manager. But ultimately, it's the company decision, and Minder tries to provide guidance to reach the best possible outcome.

There are no guarantees threat actors will keep their word, he said, but "these guys are basically running a business, and if they don't honor the agreement, then eventually no one is going to pay."

Potential bans on payments?

A new wrinkle for ransomware negotiations arrived last fall when the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control's (OFAC) issued an advisory concerning ransomware payments. In short, OFAC said making payments to entities on the U.S. sanctions list is against the law and could result in civil penalties such as fines.

While there was no policy change -- prohibiting ransom payments to sanctioned entities had been a longstanding regulation -- experts saw the advisory as an effort by the federal government to discourage such actions amid a rise in overall ransom payments.

The negotiators said paying ransoms has become much more common. Sprenger attributed the rise to the additional threat of data theft and exposure. The majority of clients for LMG have cyber insurance policies -- around 80%, which is far higher than just two years ago. And most policies will cover a ransomware payment.

Minder said he wasn't surprised by the advisory, but he saw it as a "CYA move" from the government that adds a complicated piece of the negotiation puzzle.

Sprenger said the OFAC sanctions list is a concern that negotiators and IR providers must consider. It's a routine part of the process to check the list and making sure the cryptocurrency wallet isn't on there.

But the larger concern is that, as the ransomware situation grows worse, the government may try to restrict or even ban ransomware payments. For example, Ciaran Martin, former head of the U.K.'s National Cyber Security Centre, said paying ransoms incentivizes further attacks and suggested banning such payments.

Minder said banning payments isn't the solution. "I agree -- it's subsidizing and encouraging the behavior," he said. "But to simply say 'Don't do it,' that doesn't solve the actual problem. It seems pretty tone-deaf."

He added that too many companies will be harmed and potentially put out of business if payments are outlawed. If the government institutes a ban, Minder said, then it will have to offer some kind of financial assistance or relief program for victims.

Even if the U.S. government put some sort of ban in place, Kline said he doesn't believe it will do much good. If the decision for a company is paying an illegal ransom or shutting down completely, then it will find a way to make the payment to stay afloat. Then the government will be in a thorny situation of deciding whether it wants to investigate those companies and how to penalize them.

"I don't think that's feasible," Kline said. "It sounds good on paper, but it doesn't seem enforceable in reality."

For now, the OFAC advisory is merely a reminder, but Sprenger and others are bracing for a future where their jobs as ransomware negotiators become even more complicated.

"The advisory didn't really change anything," she said. "But I would not be surprised if we start to see sanctions at the federal level."