Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023

What is the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023?

India's Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDPA) is a comprehensive privacy and data protection law that recognizes the right of individuals, referred to as data principals, to protect their personal data during the processing of that data for lawful purposes. The law culminates a seven-year journey that began when the Indian Supreme Court ruled the right to privacy was protected under the Constitution of India in 2017.

The DPDPA includes provisions regarding consent, legitimate uses, breaches, data fiduciary and processor responsibilities, and individuals' rights over their data. A person is defined as individual, undivided family, company, firm, association, the state and every "artificial juristic person." The law doesn't apply to paper data unless it's digitized or data collected for personal, artistic and journalistic use.

The law doesn't specify a timeline for enforcement, but various provisions are expected to start taking effect in 2024, as published in the government register. Fines for noncompliance range from 10,000 Indian rupees for individuals to 2.5 billion INR for organizations, or about $120 to $30,000,000.

Compared to data protection laws enacted by other countries and regions, the DPDPA contains some stylistic distinctions. The entire text uses the pronouns "she/her" to refer to data principals. Many of the law's chapters include one or more "illustrations," or examples, to describe how a provision might apply under different circumstances.

Key features of DPDPA

The DPDPA provides guidelines on processing, storing and securing personal data. It applies to all types of data linked to an individual, including name, addresses, ID numbers and behavioral information such as location, web history and preferences. But it doesn't apply to data made publicly available by an individual or third parties that post about the individual nor does it specify restrictions on publicly available data scraping, such as for AI model training. Information that an individual has consented to share is considered protected, but not data indexed by search engines or social media sites.

Data processing includes how the data's collected, recorded, structured, stored, shared or automatically acted on. This data can be processed in India or other countries unless specifically barred and applies to all companies that offer goods or services within India, regardless where their headquarters is located.

The DPDPA describes the following responsibilities of two specific entities:

- Data fiduciaries are businesses and other organizations that interact with individuals to collect, amend and delete data as requested. They need to specify why data is required, how long it's retained and how it can be used. Companies that process large amounts of data may be designated as a significant data fiduciary (SDF) and need to appoint an Indian data protection officer, conduct third-party audits and perform data protection impact assessments.

- Data processors are third-party businesses that process data on behalf of fiduciaries. They can include cloud providers or services in relation to Know Your Customer, fraud detection and credit ratings.

The DPDPA generally requires a consent process in which fiduciaries explain what data they want to collect and why, what rights users have, and how individuals can register a complaint. Guardian consent is required for disabled people and children under 18, and it's forbidden to track or monitor their online behavior. Users can also withdraw their consent, ask about data-sharing practices, and request erasure or amendment of their information. It's also illegal to impersonate another person when making requests.

Before the law goes into effect at a date to be determined, businesses must send a notice to their data principals describing the company's existing data collection practices and customer rights. Some types of legitimate data collection, such as various government and legal uses, don't require the consent of data principals.

In anticipation of the law's enforcement, organizations need to implement various technical and organizational processes to do the following:

- Facilitate consent.

- Limit usage.

- Protect data.

- Notify the Data Protection Board of India about breaches.

- Erase or amend data when asked.

- Respond to and resolve grievances.

- Manage data processing vendors.

The maximum fines for those implicated in a data breach can vary widely. Many are specified in crore, which denotes 10 million INR or about $120,000. Following is a list of the DPDPA 's maximum fines:

- Data fiduciary for not taking reasonable security safeguards: 2.5 billion INR.

- Failure to notify India's Data Protection Board and each affected data principal of a data breach: 2 billion INR.

- Child protection violations: 2 billion INR.

- Violating significant data fiduciary obligations: 1.5 billion INR.

- Individual violations, including lying, impersonation and filing frivolous claims: 10,000 INR.

Using illustrations in the DPDPA

The DPDPA uses illustrations written in simple language explaining how a given provision would apply in practice:

- Personal data not covered by the DPDPA. "X, an individual, while blogging her views, has publicly made available her personal data on social media. In such case, the provisions of this Act shall not apply."

- Personal data existing before DPDPA enforcement. "X, an individual, gave her consent to the processing of her personal data for an online shopping app or website operated by Y, an e-commerce service provider, before the commencement of this Act. Upon commencement of the Act, Y shall, as soon as practicable, give through email, in-app notification or other effective method information to X, describing the personal data and the purpose of its processing."

- Consent to process personal data without infringing on rights. "X, an individual, buys an insurance policy using the mobile app or website of Y, an insurer. She gives to Y her consent for (i) the processing of her personal data by Y for the purpose of issuing the policy, and (ii) waiving her right to file a complaint to the Data Protection Board of India. Part (ii) of the consent, relating to waiver of her right to file a complaint, shall be invalid."

- Personal data used for a specific purpose. "X, an individual, downloads Y, a telemedicine app. Y requests the consent of X for (i) the processing of her personal data for making available telemedicine services, and (ii) accessing her mobile phone contact list, and X signifies her consent to both. Since phone contact list is not necessary for making available telemedicine services, her consent shall be limited to the processing of her personal data for making available telemedicine services."

- Obligations of a data fiduciary to notify the customer. "X, an individual, opens a bank account using the mobile app or website of Y, a bank. To complete the know-your-customer requirements under law for opening of bank account, X opts for processing of her personal data by Y in a live, video-based customer identification process. Y shall accompany or precede the request for the personal data with notice to X, describing the personal data and the purpose of its processing."

- Withdrawn consent to process personal data. "X, a telecom service provider, enters into a contract with Y, a data processor, for emailing telephone bills to the customers of X. Z, a customer of X, who had earlier given her consent to X for the processing of her personal data for emailing of bills, downloads the mobile app of X and opts to receive bills only on the app. X shall itself cease, and shall cause Y to cease, the processing of the personal data of Z for emailing bills."

DPDPA vs. GDPR

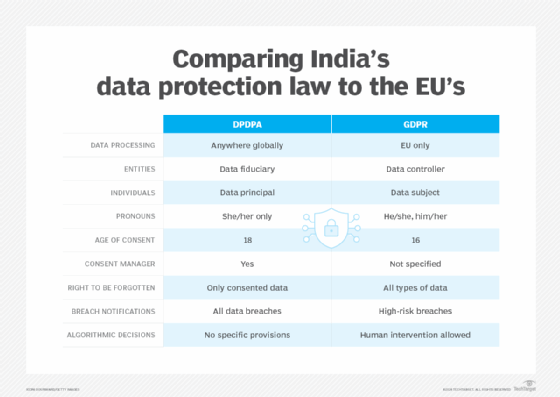

The DPDPA and the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provide a comprehensive framework for soliciting consent, defining protected data and the responsibilities of data collectors and processors, and establishing requirements to protect children. Both laws are similar in some areas, but there are notable differences.

References to some entities are slightly different, including "data fiduciary" and "data processor" in the DPDPA as opposed to "data controller" and "data processor" in the GDPR. The DPDPA goes further in some areas of data protection, such as applying the law to all personal data and not just sensitive data, recognizing more classes of individuals, requiring an older age of consent, and placing greater limits on data processing. However, the DPDPA is less stringent about international processing, limitations on government data use and the right to be forgotten. Unlike the GDPR, the DPDPA lacks a summary of guiding principles.

Types of data

Although both laws protect a wide range of personal information, the GDPR also includes additional requirements for sensitive data, such as gender, race, ethnicity, religion and health information.

Data sovereignty

The DPDPA lets companies process data overseas, while the GDPR mandates that data be stored and processed in the EU.

Definition of entities

The DPDPA defines the obligations of "data fiduciary" and "data processor," and the GDPR refers to the comparable roles of "data controllers" and "data processors," with varying requirements.

Definition of individuals

The DPDPA's rules specify people, families, groups, associations and businesses as "data principals," while the GDPR refers only to natural persons as "data subjects."

Pronouns

The DPDPA uses "she/her" pronouns only to reference a data principal throughout the document, while the GDPR uses "he/him" and "she/her" pronouns together to reference a data subject.

Fiduciary responsibilities

The DPDPA specifies requirements for SDFs that process large volumes of data and sensitive information or that could risk the rights of data principals, Indian democracy and security, and the public order. The GDPR doesn't contain such a concept.

Consent manager

The DPDPA introduces a consent manager as an entity that can act on an individual's behalf, while the GDPR contains no related concept.

Protecting children

The DPDPA limits the tracking, targeted advertising and use of data that might harm children under 18. The GDPR requires that disclosures should be understandable by children and specifies parental consent for information services to children under 16.

Right to be forgotten

The DPDPA and GDPR allow individuals to request erasure or amendment of their data. The DPDPA applies only to data collected by an organization through the consent process and no other data, while the GDPR allows an individual to request erasure of all types of information managed by a service, such as a social media provider or search engine.

Data breaches

The DPDPA requires companies to notify the data principals and India's Data Protection Board of all data breaches, while the GDPR only requires notification if the breach could pose a high risk to affected individuals.

Algorithmic decision-making

The GDPR requires algorithmic transparency and the right to request human intervention for high-stakes decisions, while the DPDPA contains no specific provisions related to algorithmic decision-making.

How the DPDPA will affect business practices

The DPDPA is a significant step toward improving the privacy and security of data for customers and businesses in India. Countries and regions in the process of establishing or updating existing data privacy frameworks might take note of how the DPDPA effectively uses illustrations in plain language to better explain some of its more complicated provisions.

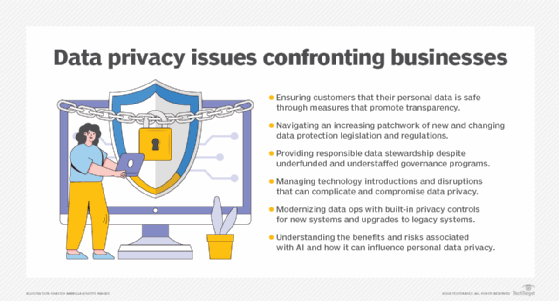

The DPDPA doesn't establish a specific timeline for when its provisions go into effect, only that the government will give notice in the official government register. Meanwhile, it will be important for all enterprises that do business in India, process Indian data or work with Indian partners to weigh the potential impact of the regulation on their operations and take appropriate actions. Businesses will need to balance legitimate data usage with data compliance.

Many organizations will be able to prepare for the transition with minor changes to existing processes already established for GDPR compliance. Others might need to consider more significant adjustments to data collection, processing, storage and governance methods, including establishing a local data protection officer.

In addition, the law's provisions on processing the data of children and managing parental consent could impact some business models. IT and data management teams might need to set up a consent management infrastructure to automate processes for erasing or amending data upon request.

George Lawton is a journalist based in London. Over the last 30 years, he has written more than 3,000 stories about computers, communications, knowledge management, business, health and other areas that interest him.