Getty Images/iStockphoto

How Harvard is approaching AI in the classroom

Generative AI is already changing classrooms and student behavior. At Harvard, that's prompting faculty to reexamine how they teach and how they assess real learning.

BOSTON -- In the moments before the opening panel at the Harvard University Generative AI Symposium, the technology was already in use.

In a Harvard Business School auditorium full of professors, researchers, students and administrators, an attendee near the front used ChatGPT to write scripts within Harvard's internal AI sandbox. A nearby programmer used the AI code editor Cursor to refine software he was using to track the day's talks.

At the university-wide event hosted by the Digital Data Design Institute at Harvard last week, there were many discussions of how generative AI could reshape education. But the tools are already quietly embedded in academic life, and there's an emerging sense that they might force conversations about what teaching and learning are really about.

The difficulty of developing consistent AI policies

Harvard students were quick to begin trying out generative AI tools, and faculty and administrators have sometimes struggled to keep up.

"Harvard isn't always known for its rapid pace," said John Shaw, vice provost for research and professor of geology and environmental science at Harvard, in the event's opening remarks. "And so that meant we did have to think creatively. We had to use imagination."

AI policies have emerged piecemeal, and sometimes not at all. Harvard's decentralized faculty structure has long supported academic freedom and innovation, but it can also inhibit the development of large-scale institutional strategies around AI.

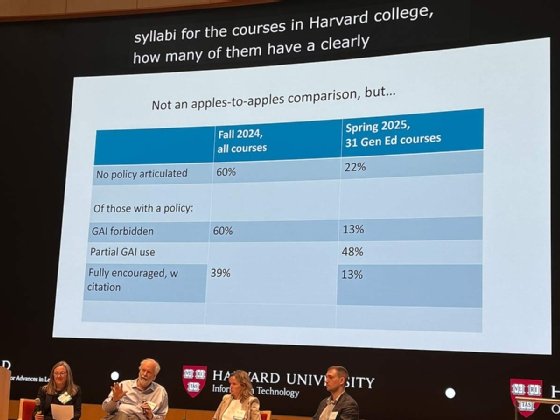

Christopher Stubbs, senior adviser on generative AI and professor of physics and astronomy at Harvard, cited data showing that many Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) professors did not include AI use guidelines in their course syllabuses in fall 2024 and spring 2025, despite administrative requests.

"Our attempts to instill in the Harvard FAS faculty a sense of obligation to articulate a clear policy to our students essentially failed," he said.

In practice, some professors actively encourage students to experiment with generative AI, while others forbid it, and many fall somewhere in between. Harvard Business School assistant professor Iavor Bojinov teaches an "AI-native" course that integrates the technology as a core component; on the other end of the spectrum, a professor in the FAS history department mentioned during a breakout session that she'd first used AI that same week, to prepare for the symposium.

The larger issue, faculty members say, is that students are already using AI, for better or worse. And the presence of these tools is already altering how they approach learning. If institutions like Harvard don't move quickly to define clear, thoughtful strategies around generative AI, they risk letting the tools -- rather than educators -- determine how students learn.

How the ease of AI shortcuts can challenge learning

One of generative AI's biggest selling points is making difficult, time-consuming tasks fast and easy. In education, that's exactly the problem. Effective learning involves persevering through difficulty and developing the ability to think independently -- precisely the skills that AI can shortcut.

At Harvard Business School, Bojinov helped redesign the course Data Science and AI for Leaders to intentionally center generative AI tools, including an automated tutor chatbot and the data science assistant Julius AI. Students embraced the tools, with some even using them outside class, Bojinov said, such as one student who used Julius to help a nonprofit build data-driven models to improve donor outreach.

But the qualities that make AI attractive have tradeoffs. "In some of our early surveys ... we've seen people are very positive about these tools, but -- and this is something we really need to address -- it made it so easy for them to cheat," Bojinov said in an interview with Informa TechTarget.

Some students were strikingly candid about how generative AI could undermine their learning. Bojinov recalled his surprise when one student approached him after class, confessing that the AI tools had made coursework "so easy that I don't have to think."

In a breakout session, Harvard Medical School professor Adam Rodman described similar dynamics with his students, who were also conflicted about their own AI use. "They use it all the time -- that didn't surprise me," Rodman said. What did surprise him was their simultaneous recognition that the tools might be harming their cognitive skills.

"They literally were telling me, 'I think this is making me dumber, but I have to keep using it because I have so many other things to do,'" he said.

That mix of pragmatism and unease seems to characterize the way many students approach generative AI. As Rodman and Bojinov both pointed out, these are students juggling nonstop demands: coursework, clinical or extracurricular responsibilities, job applications, the daily work of being a person. Viewed through that lens, AI might function more as a coping mechanism.

"I thought people would be intrinsically motivated to still go and learn these things because they're important," Bojinov said. "I think the reality is, when you make it so easy and people have so many competing interests on their time, they're going to take the easy way out."

The problem, then, goes beyond whether to permit AI in the classroom. The real question is how to support meaningful education in an environment where shortcuts are always available. As Bojinov put it, it's like choosing between fast food and cooking something healthy.

"How do you put the incentive structure around it to prevent that, so that maybe they go and pick up some vegetables instead of just getting a Big Mac?" he said.

AI offers a chance to question norms in education

Some faculty see the omnipresence of generative AI as a chance to ask overdue questions about education itself. AI tools raise concerns about cheating and cognitive offloading, but they can also expose real weaknesses in how students are currently taught and assessed.

"I think this shines a spotlight on things that were already problematic and accentuates them," Stubbs said.

Generative AI can instantly generate explanations, summaries and passable analysis. These models still hallucinate -- a problem that might be getting worse, not better. But they return enough correct answers on widely covered topics that the utility is likely to outweigh the risks for many students.

Especially during high-pressure periods like finals, when time is short and perfection isn't essential, a "good enough" answer can feel sufficient. After all, human writing, thinking and factual recall aren't flawless either, and those processes require far more effort.

Nonie Lesaux, professor of education and dean of the faculty of education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, warned in a panel that AI pushes students toward quick conclusions rather than careful reasoning, creativity or cognitive flexibility.

"Access to information is not the same as learning," she said. "And it is certainly not the same as active learning and sustained learning."

Real learning depends on slower, often messier processes like self-regulation, impulse control and sustained attention. And those cognitive muscles were already weakening before the generative AI boom.

"We have a very different learner in certain ways on our hands, even in the last, say, 15 years," Lesaux said. Even before the pandemic, she noted, students were showing signs of diminished executive function: impaired focus, less impulse control, a reduced ability to reflect and self-regulate. AI didn't cause that decline, but it could accelerate it.

At this point, banning AI outright is unlikely to work, whether instructors want to or not. The tools are already widely in use, and current detection methods are unreliable. Even when instructors suspect that a student's work was generated by AI, it's often hard to prove, and AI detectors can raise false positives for neurodivergent writers and people for whom English is a foreign language.

Instead, educators will need to design learning environments that encourage students to pause, reflect and think more critically. "Big picture, the design challenge here is that we want to support our learners ... to go deeper, to slow down," Lesaux said.

AI as a diagnostic tool for teachers

In a breakout session, Harvard Kennedy School professor of public policy Sharad Goel described how when he reviewed anonymized transcripts from his course's customized chatbot, he noticed something striking: Students in his class felt comfortable asking an AI chatbot basic questions they weren't bringing to office hours.

"The questions that they are asking [the AI] are qualitatively different from the questions that they come to office hours to ask me," he said. "When I started reading these things, I was like, 'Oh, I didn't know that they didn't know this.'"

Goel realized that, for years, some students had likely been lost in the early weeks of his courses without saying anything. Now, the chatbot logs were surfacing that confusion to him -- a revelation he said was surprising and somewhat frightening, as an educator.

"A large portion of students were probably confused with ideas that were introduced at the beginning of the class ... and then they still weren't understanding at the end," Goel said. "And I don't think I fully grokked that until relatively recently. But now, once I understand that, it's much easier to intervene."

The chatbot data enabled Goel to identify difficult concepts and revisit them more deliberately in class. He now builds in time at the start of each lesson to review those areas and shares a weekly AI-generated summary of trends in student questions with his teaching team.

AI as an opportunity to rethink assessment

Stubbs expressed concern about what generative AI means for traditional assessments, particularly narrative-driven formats like essays and personal statements.

He illustrated the challenge with an anonymized graduate school application essay. Although Harvard had banned generative AI use in the application process, the submission showed signs of AI authorship -- not just the almost comically generic language, but placeholders like "[Professor's Name]" that had been left unfilled.

"If ever there was an indicator that narrative is no longer a reliable indicator of communication proficiency or competence, here's a clear example," Stubbs said.

Andrew Ho, a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, suggested reflecting on what assessments are meant to measure. Rather than relying on written exams, he proposes "conversational celebrations of learning" -- in-person oral evaluations, structured as back-and-forth conversations that test understanding, adaptability and real-time reasoning.

Such assessments, of course, have the advantage of requiring skills that large language models can't replicate. But their value goes beyond AI-proofing, Ho said in a breakout session. Conversational assessments reward the kind of contextual thinking and self-expression that students will need in the real world.

"It's less about avoiding AI than uplifting conversational fluency," he said. "Conversation is underassessed [and] undervalued, in my opinion, and we can do more to elevate it."

Stubbs is also shifting his assessment approach, he said in a panel. He plans to go analog for his fall term's final exam -- a classic blue book exercise, no electronics allowed. Like Ho, he sees the value not only in the format itself, but in the clarity it provides. If students know what kinds of thinking will be required at the end of the course, instructors can build in appropriate scaffolding throughout.

Bojinov, meanwhile, pointed out that written assignments have never been a truly neutral measure of insight. Naturally strong writers and native English speakers have long had an advantage, he noted, regardless of whether their ideas were actually more accurate or original than those of their peers. And with AI tools changing how students complete written work, faculty now have a clearer view of where traditional systems might have privileged style over substance.

Today, "if you're just asking for an essay, people will just write an essay using generative AI," Bojinov said. "But the point of asking them to write an essay in the past was to do this more critical thinking. I think there are other ways of getting to that without it being an essay."

Teaching skills like critical thinking, metacognition and verification has always been difficult. Generative AI makes it harder, but it also clarifies what's at stake. Addressing these challenges could help instructors find education approaches that are more durable and meaningful than what existed before.

"[AI] forces you to confront a hard question, which is: Just exactly what am I trying to do in this course?" Stubbs said. "How am I trying to influence student thinking? How am I going to assess it? And how are we going to know if we succeed?"

Lev Craig covers AI and machine learning as the site editor for SearchEnterpriseAI. Craig graduated from Harvard University with a bachelor's degree in English and has previously written about enterprise IT, software development and cybersecurity.