B2B (business to business)

What is B2B (business to business)?

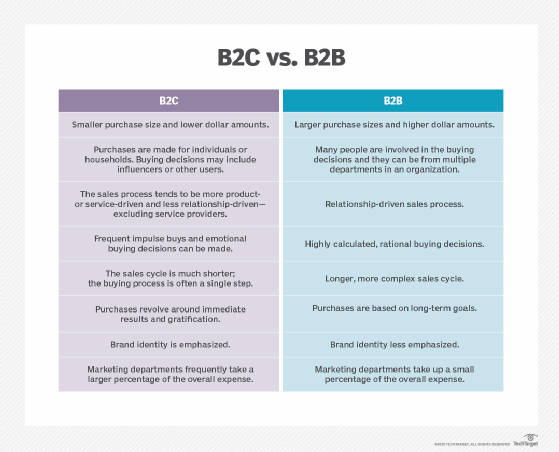

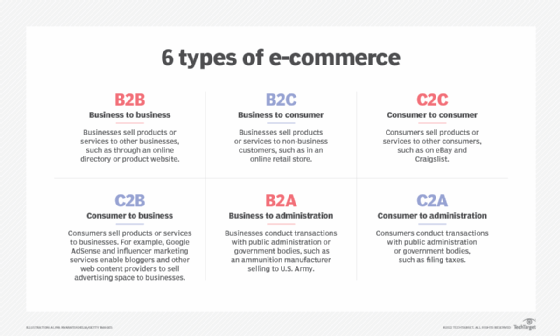

B2B (business-to-business) is a type of commerce involving the exchange of products, services or information between businesses, rather than from a business to consumer (B2C). A B2B transaction is conducted between two companies, such as a wholesaler and an online retailer. In most B2B commerce, each organization benefits in some way and typically has similar negotiating powers.

The U.S. Department of Commerce's International Trade Administration forecasts that global B2B e-commerce will reach $36 trillion by 2026, representing a compound annual growth rate of 14.5% over a 10-year period.

Nearly all B2B commerce occurs on the internet as e-commerce. Transactions are conducted via different categories of websites, including the following:

- Company websites. This is the most straightforward model of B2B transactions. A company uses its own website to sell goods and services directly to its business clients. Sometimes, a company website uses a secure extranet to provide clients with exclusive access to product catalogs or price lists.

- Product supply and procurement exchanges. These online exchanges allow a company's purchasing agent to shop for supplies or raw materials from multiple vendors, submit requests for proposals (RFPs) and, in some cases, bid on products. Also known as e-procurement sites, these exchanges can serve a range of industries and be tailored to niche markets.

- Specialized or vertical industry portals. These portal sites provide specialized and vertical markets with a more targeted approach than procurement sites. They might also support buying and selling, and provide information, product listings, discussion groups and other features for industries such as healthcare, banking and transportation.

- Brokering sites. These sites act as an intermediary between service providers and potential customers that need their services, such as leasing equipment or services.

- Information sites. Sometimes known as infomediaries, these sites provide information about a particular industry to companies and their employees. Information sites include specialized search sites and those of trade and industry standards organizations.

Many B2B sites fall into more than one of these groups, and the models for B2B sites are continually evolving. In fact, the B2B market includes companies that sell software for building B2B websites, including tools, templates, databases, methodologies and transaction software.

This article is part of

What is iPaaS? Guide to integration platform as a service

- Which also includes:

- middleware

- Pros and cons of the 4 best IPaaS software options

- B2B (business to business)

How does B2B work?

In a B2B transaction, one business, often referred to as a vendor, sells products or services to another business. Typically, a sales team or department conducts these transactions, rather than the entire enterprise or a single person. Occasionally, one person on the buyer side makes a transaction in support of the company's business goals. Conversely, some B2B transactions involve the entire company's use of a product, such as office furniture, computers and software licenses.

For larger or more complex purchasing decisions, a buying committee handles the B2B product selection and decision-making process. These committees typically include the following personnel:

- A business decision-maker, such as the person responsible for the budget.

- A technical decision-maker who evaluates the capabilities of the prospective products.

- Influencers, such as individual users and employees who provide input on how the product will be used.

Large purchases might involve an RFP, in which the buyer invites prospective vendors to submit proposals detailing their products, contractual terms of service and pricing.

Why is B2B important?

Every business needs to purchase products and services from other businesses to launch, operate and grow. B2B commerce supports these activities. A company uses B2B suppliers to procure products and services, such as the raw materials they need for production, office space, office furniture, computer hardware and software. The food that companies stock in their kitchens and the signs displayed on their office buildings are also examples of products and services purchased from suppliers.

B2B suppliers are more likely to engage in long-term business relationships with their customers compared to B2C companies. B2C transactions often involve ad hoc purchases from individual consumers, whereas B2B suppliers can expect more frequent and predictable purchases from businesses for goods and services. Many B2B suppliers sell specialized and customized products tailored to businesses' specific needs.

Examples of B2B marketing strategies

B2B companies have various methods for reaching their target audiences. Digital communications has enabled these strategies to increasingly go online and let companies expand their reach. These strategies include the following:

- Search engine optimization (SEO). Knowledge of SEO lets B2B companies improve the ranking of their websites in search engine results. In the same vein, pay-per-click advertisements let companies have their messages easily seen on search results pages.

- Content marketing. Different content forms, such as articles or videos, can promote a B2B company's message to the right audiences and boost a webpage's search engine rank.

- Social media marketing. Understanding which social media platforms a given audience is using enables B2B companies to tailor their social media strategies around that knowledge.

- Web design. Digital marketing agencies and in-house web design experts can create customized websites for B2B organizations to use to target customers.

- Email marketing. Email marketing campaigns can be effective when orchestrated correctly and targeted at the right customers.

- Influencer and word-of-mouth marketing. Prominent figures or even everyday people can spread the message that a certain B2B company is ideal for certain customer groups.

- Account-based marketing (ABM). Organizations home in on a group of high-value customer accounts in an industry and tailor their services to that group's needs. Customer relationship management (CRM) functionality and platforms such as Salesforce are conducive to ABM.

Types of B2B companies

There are several types of B2B companies, including the following:

- Producers design, create and manufacture their own products. They might sell their products directly to businesses or indirectly through retailers or resellers.

- Retailers and resellers sell products and services made by other companies directly to businesses online, from physical stores or both.

- Agencies and consultants provide advice, oversight and subcontracted work to businesses. For example, an advertising agency might manage and execute a multimillion-dollar advertising budget for a consumer brand. A digital marketing agency might design and build a website and mobile app for the same client.

B2B industries

B2B companies operate in many industries and markets. The following are a few notable examples:

- Financial services. Banks, accounting firms and other financial services providers offer commercial lending, payment processing, commercial tax preparation, investment banking and similar services to business clients.

- Technology. Hardware, software and cloud services are vital for nearly every business, and business users often have unique technology needs. Examples include CRM software, data center infrastructure and cloud-based human resource management.

- Office supplies. Businesses rely on these suppliers for large-volume purchases of items like paper, ink cartridges and file storage.

- Manufacturing. Unlike other sectors, manufacturing is almost entirely a B2B market. Manufacturers sell materials, components and parts to other businesses that, in turn, use them to create new products. For example, a semiconductor manufacturer's primary customers are companies that use chips to build computers, printers, mobile phones and other more advanced products.

- Marketing and advertising. Marketing and advertising agencies largely serve business clients, making B2B commerce a cornerstone of their business model.

From caterers to construction companies, B2B commerce is prevalent throughout many other industries, including retail, telecommunications, insurance, healthcare, education, real estate, construction, engineering, and food and beverage services.

Benefits of B2B

The B2B market has many benefits compared to B2C, including the following:

- Larger average deal size. A B2B company can grow B2B sales with a smaller number of high-value deals compared to a B2C company, which might require thousands or even millions of individual sales to stay profitable.

- Greater customer loyalty. Another key difference between B2B and B2C is that B2B customers are less inclined to change vendors, because it's operationally disruptive and expensive to do so. Conversely, B2C customers have less incentive to stay loyal to one brand if a competitor offers a more convenient, inexpensive or otherwise appealing alternative, resulting in large churn rates.

- Diverse market entry options. B2B companies can target enterprises across many industries and geographies, resulting in a larger market opportunity. Alternatively, they can specialize in one industry, such as technology, and become leaders in that niche.

- More predictable buying cycles. Business clients are typically more consistent in their purchasing habits than consumers. A hospital always needs to regularly restock its supply of catheters and syringes, whereas many consumer purchasing decisions can be delayed and unpredictable.

- Faster delivery. Because B2B e-commerce tools make the sales process efficient for sellers, they accelerate the process for buyers. Integrated systems enable the transacting companies to sync data across channels, automate fulfilment and inventory updates, and manage complicated orders.

- Built-in order management. Cloud-based e-commerce platforms easily integrate with back-end order management systems. This enables B2B sellers to synchronize order inventory and customer data across every channel.

B2B challenges

B2B e-commerce has some challenges, such as the following:

- Slower decision-making. B2B customers rarely, if ever, make impulse buys. Purchasing decisions are more likely to become drawn out as many stakeholders get involved in the process, clients need to obtain budget approval and other business needs take priority.

- Price negotiation. Because B2B buyers buy in bulk or make much more significant investments, they typically negotiate for better prices, ask for discounts and expect extra services.

- E-commerce supply chain complications. Supply chain management in e-commerce is complicated when multiple partnerships are involved. Miscommunication or disruption at any point in the supply chain can slow down the process.

Examples of B2B companies

B2B companies conduct business either online or at physical stores and distributors. They are some of the largest companies in the world, but many small businesses are also B2B companies. These companies work across practically every industry, and a lot of B2B businesses, such as Amazon and Apple, are also B2C businesses.

According to Wrk Technologies, a provider of workforce management software and consulting services, the largest B2B vendors include several information technology (IT) companies, such as Microsoft, IBM and Adobe. Some of the largest non-IT B2B companies are UPS, Wells Fargo and General Electric.

Learn how customer communications management, facilitated by generative AI and other technologies, is key to improving customer experience success for B2B and B2C businesses alike.