Risk appetite vs. risk tolerance: How are they different?

Risk appetite and risk tolerance are related, but they don’t mean the same thing. Not knowing the difference can cause big problems for your risk management program.

Enterprise risk management programs have the ambitious governance goal of identifying, evaluating and managing all the risks facing an organization.

To do so effectively, enterprise risk management (ERM) programs must have a consistent process for identifying the types of risk their organizations face, for assessing the level of risk each type poses, and for understanding how each risk contributes to the maximum risk the organization is willing to accept.

As the people involved in ERM programs undertake these evaluations of risk exposure, they use two important and related terms: risk appetite and risk tolerance.

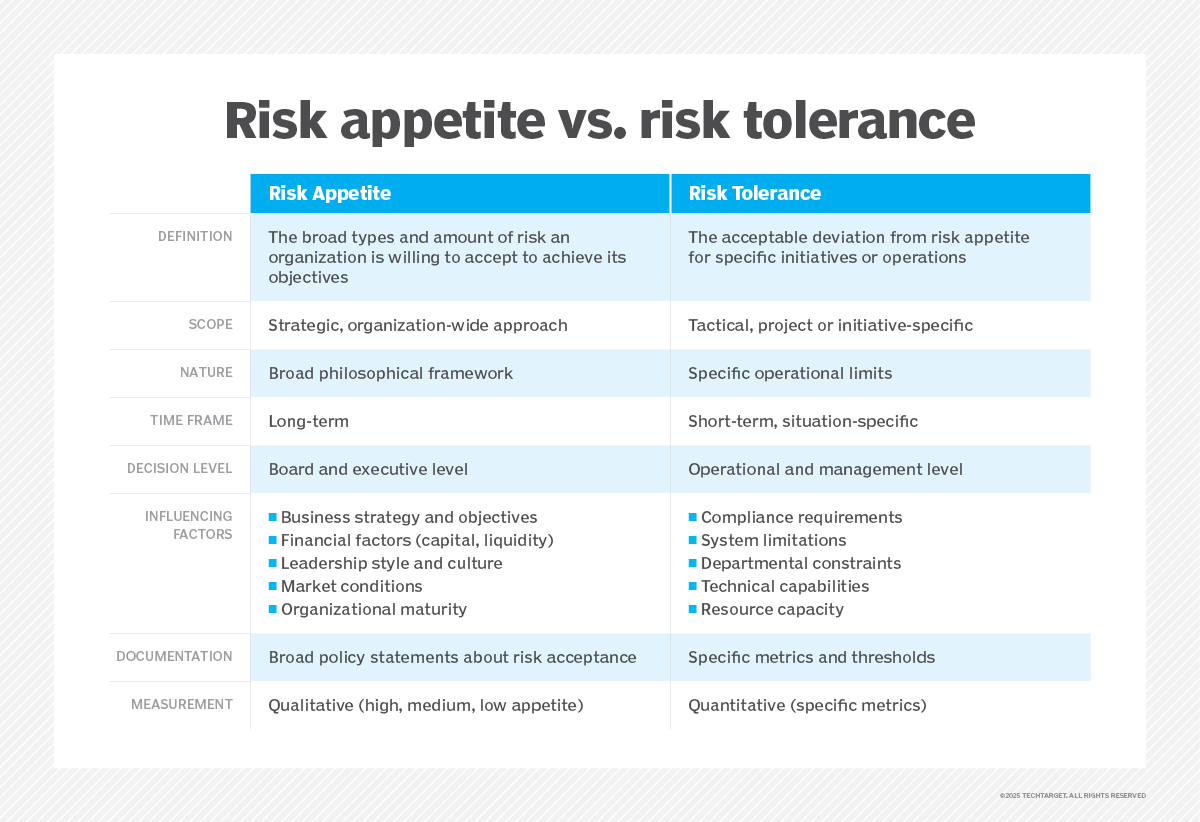

While the concepts are related, they represent two different ways that risk managers describe their organization's risk attitude -- described by ISO 31000:2018 as the organization's general approach to assessing and subsequently pursuing, retaining, taking or turning away from risk.

Mixing up risk appetite with risk tolerance can result in taking too little or too much risk, misallocating resources and potentially facing regulatory issues or financial losses. Let’s look at risk appetite and risk tolerance and break down how they relate to and differ from each other.

What is risk appetite?

Risk appetite is best described as the types and amount of risk a company is willing to accept to achieve its objectives. Organizations recognize they can't remove all risks from their business operations. Achieving their business goals requires accepting some risks while mitigating, avoiding or transferring others.

ERM programs determine which risks fall within the organization's risk appetite and which require additional controls before they're acceptable.

The following factors can influence an organization's risk appetite:

- Business strategy and objectives such as growth targets, market expansion plans and innovation.

- Financial factors include available capital, liquidity levels, revenue stability and profit margins.

- Leadership style, organizational maturity, company size and age, historical risk experience and other culture elements.

- Market conditions such as the economic climate, industry trends, regulatory environment, technological changes and competitive landscape.

What is risk tolerance?

Risk tolerance is the amount of acceptable deviation from an organization's risk appetite. You can think of an organization's risk tolerance for a specific initiative as its willingness to accept the risk that remains after all relevant controls are put in place.

Factors that determine an organization's risk tolerance include the following:

- Compliance issues such as reporting requirements, legal constraints and mandatory capital reserves.

- System limitations such as technical capabilities and resource capacity infrastructure limits.

- Departmental factors such as business-unit specific objectives, performance targets and operational constraints.

Understanding the relationship between risk appetite and risk tolerance

Risk appetite is the broad, strategic philosophy that guides an organization's risk management efforts, while risk tolerance is a much more tactical concept that identifies the risk associated with a specific initiative and compares it to the organization's risk appetite.

In other words, an organization determines its risk appetite as part of a strategic effort to understand and manage risks. It determines risk tolerance on a case-by-case basis as it evaluates the specific risks associated with a given initiative.

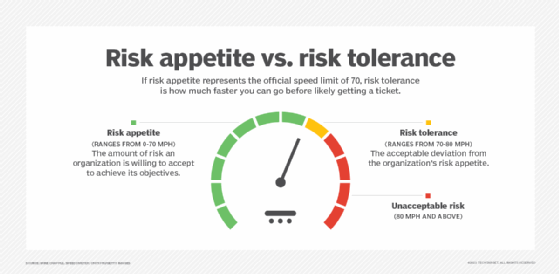

One way to understand this relationship is to think of the risks associated with fast driving. Governments around the world recognize that fast drivers create a level of risk to all other drivers on the road. The faster a motorist drives, the more risk is created. To control this risk, governments set speed limits. The lower the speed limit, the lower the risk to motorists.

However, lower speed limits also inhibit the flow of traffic, preventing vehicles from quickly reaching their destinations. Governments must balance these concerns and determine the appropriate rate of speed for different types of roads. Speed limits are, therefore, statements of the government's risk appetite.

On highways today, however, most drivers exceed the posted speed limits. Police officers charged with enforcing these limits usually let motorists do so, as long as they aren't traveling at speeds far beyond the posted limit. A police officer patrolling a road with a 70-mph limit might, for example, decide to only pull over vehicles traveling at 80 mph or faster. This is an example of risk tolerance: The officer, presumably with the approval of superiors and government officials, is willing to tolerate deviations of up to 10 mph from the posted speed limit.

Examples of risk appetite and risk tolerance statements

While speed limits are an excellent conceptual example for describing risk management considerations, in practice, most of the risk decisions made by organizations are not so easily quantified. Instead, they rely on subjective evaluations of risk made by business leaders in consultation with subject matter experts. These evaluations and decisions are documented in statements of the organization's risk tolerance and risk appetite.

Risk appetite sample statement

An ERM committee might make the following statement about the organization's risk appetite:

Our organization understands that there are risks inherent in our business and that taking risks is a prerequisite to achieving our strategic objectives. Our enterprise risk management program methodically evaluates risks using a cost/benefit approach and determines appropriate risk treatment strategies. As an organization, we have a low appetite for risks that involve the possible loss of personally identifiable information about our customers and employees and a moderate appetite for risks that involve the potential for financial losses or cybersecurity breaches that do not involve PII but may be impactful other business objectives.

The ERM committee might extend this risk appetite statement to include all of the different types of risk facing the organization and then use it to craft more specific risk tolerance statements about individual business initiatives under consideration.

Risk tolerance statement examples

For example, the committee might find that a specific project is within the organization's risk appetite and issue the following statement referencing its risk tolerance:

The ERM committee evaluated the risk of implementing project X and determined that it has a low probability of creating the potential loss of PII. It is, therefore, within our risk tolerance.

But another project might exceed the organization's risk tolerance. In that case, the ERM committee might suggest that the project team revisit the relevant risks and implement new controls to mitigate, avoid or transfer the risk to bring the project to an acceptable risk level. The risk tolerance statement for that project might read like this:

The ERM committee evaluated the risk of implementing project Y and determined it would create a situation of high financial risk that is outside our risk tolerance. Controls must be put in place to mitigate this risk to an acceptable level prior to initiating this project.

The examples above illustrate how identifying and documenting risk appetite and risk tolerance is a crucial step in an organization's road to developing a mature risk management process. The risk appetite statement provides a yardstick for the consistent measurement and evaluation of risks and paves the way for using associated risk tolerance statements to better guide future risk mitigation work.

Risk appetite vs. risk tolerance: Confusing these terms can lead to problems

Risk appetite is the broad level of risk an organization is willing to accept in pursuit of its goals, while risk tolerance is the acceptable deviation from those risk levels. Mixing up these two concepts can lead to poor strategic decisions, financial losses and compliance issues. Here are three hypothetical scenarios.

Retail

- A retail chain mistakes its inventory shrinkage tolerance -- 1% of stock -- for its overall risk appetite in operations.

- This confusion results in implementing excessive security measures that frustrate customers while neglecting broader risks like changing consumer buying habits and competition from e-commerce.

Healthcare

- A hospital network confuses its risk tolerance -- a maximum patient wait time of 30 minutes -- with its overall risk appetite for patient care quality.

- Focusing on speed results in rushed diagnoses, medical errors, lawsuits and regulatory penalties.

Banking and financial services

- A bank misinterprets its credit risk tolerance limits -- e.g., maximum default rate of 3% -- as its risk appetite, leading it to approve every loan application that falls under this threshold.

- This confusion leads to the bank accumulating too many high-risk loans that individually meet the tolerance threshold but that, in total, create an unsustainable risk level, potentially leading to a liquidity crisis.

-- Informa TechTarget editors

Mike Chapple is academic director of the Master of Science in Business Analytics program and teaching professor of IT, analytics and operations at the University of Notre Dame.

Editor's note: Mike Chapple wrote this explanation of risk appetite vs. risk tolerance in 2021. It was reformatted in 2023 to improve readability, and in 2025 a sidebar and chart were added by Informa TechTarget editors.