Getty Images

How to navigate data sovereignty for AI compliance

As AI systems consume data for training and decision-making, businesses must navigate complex regulations, geopolitical boundaries and vendor risks.

Global enterprises have spent a decade migrating their architectures to the cloud for agility and scale. Now, many are deliberately building constraints into that same architecture to meet data sovereignty requirements. So, what is data sovereignty? And why is it so critical for AI compliance?

Data residency was once a checkbox for IT, mainly to establish compliance with data privacy regulations, such as the European Union's GDPR, which applied in specific jurisdictions. Data residency is a simple concept: it refers to the physical location where data is stored.

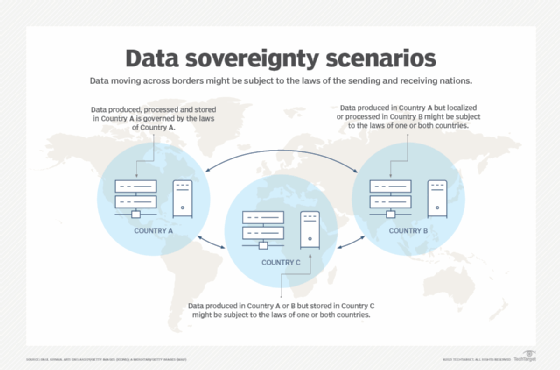

Data sovereignty, however, involves more than identifying where data resides. It also concerns who has legal authority and practical control over data, regardless of where it resides. Data residency asks, "Where are the servers?" Data sovereignty asks, "Whose laws apply to this data?" and "Who holds the keys?"

Data sovereignty for AI comes with its own complexities. AI doesn't just store data like a database or analyze it like a business intelligence (BI) system. AI consumes data for training and takes actions based on it, so data sovereignty for AI must cover where the model is trained, where inference occurs and who controls the encryption keys throughout the entire process.

Now a boardroom priority, data sovereignty for AI shapes not only storage, but also which AI capabilities a business can deploy in which markets. Given the recent uptick in AI systems across enterprises, many of which are global, businesses are beginning to navigate the sovereign cloud for their AI systems, implementing infrastructure options designed with data sovereignty in mind.

What is driving AI data sovereignty?

Given the advantages of cloud computing, it might seem strange that organizations now seek to limit data interoperability and agility, but there are good reasons for doing so. These three factors are increasing the need for AI data sovereignty:

- Regulatory pressure. The GDPR, California's CCPA, industry-specific rules such as HIPAA and many other data regulations worldwide now apply to AI model training and inference in addition to data storage.

- Geopolitical fragmentation. Some countries require that categories of data deemed relevant to national security remain within national boundaries. Others scrutinize data or model transfers to particular countries, depending on geopolitical risk or data protection laws.

- Third-party model providers. Technologies such as BI or predictive analytics were built on models of an organization's data, using data warehousing techniques for BI or statistical models for prediction. These models were crafted in-house, even if they were deployed in the cloud. However, with AI, it's often the vendor's cloud-based AI service that trains models. Thus, there's growing concern that patterns derived from personal or proprietary data might persist in AI models in ways that businesses can't easily detect or delete.

Core components of AI data sovereignty

To address compliance concerns, a workable strategy for AI data sovereignty must support five governance capabilities:

- Data residency and localization address the physical location of data, whether at rest or in transit. Compliance often requires that certain types of data never leave a specified jurisdiction.

- Model training and the location of inference extend the concept of residency from data to computation. Storing data in-country offers limited protection if training jobs are run on servers outside the country.

- Data access controls specify who can query data, under what conditions and how to audit access and use.

- Encryption and key management determine who manages cryptographic keys. Hold your own key architectures give the business control over its encrypted data, meaning the cloud provider can't decrypt it, even if a court or government demands it.

- Auditability and transparency require documentation of data provenance across the AI lifecycle. Regulators increasingly expect organizations to demonstrate compliance, not merely assert it. Detailed logs of training data and inferences become evidence in audits.

The sovereign cloud landscape

With growing demand for data sovereignty in AI, businesses are turning to various approaches to ensure compliance. While there is no single approach that covers all concerns, some broad patterns emerge that businesses can evaluate:

Most businesses should adopt hybrid strategies for AI data sovereignty, matching their architecture to the sensitivity and regulatory profile of each workload. The premise is straightforward: Not all data carries the same risks or is regulated with the same level of strictness, so it doesn't all have to be handled the same way.

A business might keep some data strictly on-premises -- often personally identifiable information or data relating to corporate intellectual property. But they might have a large amount of less sensitive data, such as documentation, public-facing marketing content or data licensed from third-party providers. They can store less-sensitive data in the cloud and use it for various tasks, such as training large language models.

AI lifecycle implications

While data sovereignty is increasingly non-negotiable for AI systems, it also carries implications and challenges across the AI lifecycle. For instance, working with restricted data sets during training can complicate model development. If data can't leave a specific jurisdiction, such as California or Europe, how can an international business train a model that represents its business globally?

Federated learning offers one answer. Models learn from decentralized sources without the raw data ever leaving the local systems. A local system trains a copy of the model on its own data and produces an updated parameter set. It's those parameters, not the underlying data, that are moved to a central coordinating server where a global model is aggregated. This approach might require several cycles to create a converged model.

Another implication that businesses must consider is documentation, as auditors will ask where the data came from and how it changed along the way. Documentation must answer both questions.

Dependence on third-party models, especially those hosted in the cloud, also adds data risk. Contractual "do not train" clauses forbid a vendor from using customer data for training. These clauses might provide legal protection, but some jurisdictions don't recognize them. Enterprise-grade technical controls provide more certain restriction.

Lastly, when it comes to AI, output from generative AI or actions from agentic systems might reveal patterns learned from regulated data, even if the data itself isn't reproduced. As a result, regulators are increasingly imposing requirements on AI-generated materials.

Architecting data-sovereign AI systems

The potential complexity of the sovereign cloud for AI might seem daunting. But some practical steps can guide implementation:

- Begin with classification. Know which data falls under sovereignty requirements before selecting infrastructure.

- Match architecture to the level of risk. Not every workload demands maximum control. First, balance sovereignty with regulatory requirements. Then, weigh that against scalability, performance and cost.

- Embed governance from the start. As AI adoption spreads and scales, policy-aware pipelines and machine-readable governance rules can reduce friction. It is much easier to design governance from the beginning than to retrofit it to deployed architecture.

- Design for adaptability. Regulations are evolving and will likely get more demanding. Architecture built only with an eye on today's rules will require costly rework.

In this environment, the sovereign cloud is a source of trust. Customers and partners need confidence that their data is secure and that sensitive details don't leak into unmanaged AI models. Organizations that can prove both gain a valuable edge.

Donald Farmer is a data strategist with 30-plus years of experience, including as a product team leader at Microsoft and Qlik. He advises global clients on data, analytics, AI and innovation strategy, with expertise spanning from tech giants to startups.