Getty Images

Does AI-generated code violate open source licenses?

Unresolved questions about how open source licenses apply to AI models trained on public code are forcing users, vendors and open source developers to navigate legal gray areas.

Using generative AI effectively in the enterprise involves navigating a range of challenges, from ensuring training data quality to fine-tuning models and mitigating security risks.

Another challenge -- easily overlooked, but potentially profound -- is open source software licensing. Many generative AI systems are trained on vast amounts of internet data, some of which comes from open source code repositories. That raises concerns about potential license violations related to both training data and generated output.

Although it remains unclear under what circumstances generative AI technology might violate open source licenses, courts may eventually rule that it does, posing legal and compliance risks for businesses. Organizations should understand how open source licenses intersect with AI, stay informed on relevant lawsuits, and consider how both open source developers and enterprise users can adapt to protect their interests.

LLMs and open source software licensing

Most of today's leading large language models (LLMs), such as those developed by OpenAI, Meta and Google, are trained on vast troves of data collected from the internet. These data sets often include open source code hosted on platforms like GitHub.

Training on open source code enables LLMs to generate new code, a core feature of products like GitHub Copilot, ChatGPT and Claude. But just how "new" that code is remains up for debate; it's arguable that the code generated by AI tools isn't truly new, but rather a regurgitation of their training data.

Open source software is generally free to use and modify, so no one disputes that LLM developers were allowed to access it without paying. The controversy stems instead from how AI models use that code. More specifically, some argue, LLMs reproduce code in ways that could violate open source software licenses.

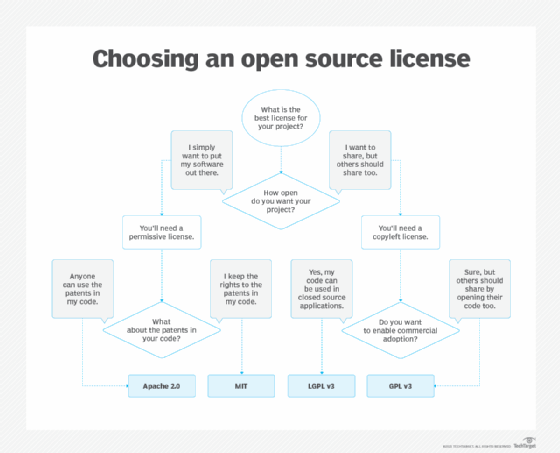

Licensing terms vary across the dozens of open source licenses in existence today. But some -- most notably the GNU General Public License, more commonly known as the GPL -- require that developers who publicly use a modified version of open source software also release their modified source code. Some licenses also require attribution to the original authors of open source code when releasing software that incorporates or reuses that code.

How open source software licenses affect AI

Historically, open source licenses were designed under the assumption that code reuse or modification meant developers were manually inserting the code into applications they were otherwise building from scratch. Under those circumstances, complying with open source licenses is relatively straightforward.

But the rise of LLM-assisted software development complicates that picture. Say a developer uses an LLM to generate code for an application, and that model's ability to generate the code hinges on its own training on open source code. Does that mean the developer is reusing that open source software because they used an LLM to help write their application's code?

Some argue yes: Any application developed with assistance from AI must comply with the licenses governing the code the model was trained on. Others disagree, contending that open source licensing requirements shouldn't apply because LLMs don't reuse open source code in the conventional sense. Although LLMs were trained on open source code, the argument goes, they don't create verbatim copies of it -- except when they do, which is rare but reportedly happens.

This issue is relevant, by the way, whether the LLM in question is open source, proprietary or something in between. Meta's Llama models, for example, are branded as open source, but some critics argue that they fail to meet the definition of truly open source AI. The debate about AI and open source software licensing focuses not on the code within LLMs themselves, but rather the data they were trained on.

The difficulty of determining open source license violations

Determining whether LLMs violate open source software licenses is challenging for several reasons:

- Lack of legal precedent. No court has yet ruled on whether training an LLM using open source code constitutes reuse or modification under open source licenses or whether doing so would violate those licenses.

- Ambiguity of reuse. Developers interact with LLMs in varied ways that have different implications for compliance. For example, a developer could ask an LLM to write "new" source code and incorporate it directly into an app without making any modifications. They could use LLM-generated code as guidance, but ultimately write their own code. Or they could do something in between, modifying some LLM-generated code while using other parts verbatim.

- Lack of training data transparency. Most pretrained LLMs, including many labeled as open source, don't publicly disclose their training data. Without that information, it's impossible to know exactly what code a model was trained on and thus which open source licenses apply.

- Hosting platform terms of use. Platforms like GitHub make publicly shared code broadly accessible but don't usually specify whether that code could be used for AI training -- by the platform's owner (Microsoft, in the case of GitHub), a partner or a third party. Open source developers could therefore argue that their code was used for model training without their consent. But platform owners and AI companies might counter that developers of publicly posted code should expect it to be reused, including for model training.

Given these uncertainties, it's currently impossible to say definitively whether using generative AI to help write software violates open source licenses. Much is likely to depend on how exactly developers use AI.

For example, courts might rule that license obligations are avoided if developers significantly modify AI-generated code. Alternatively, they might require proof that a model was trained solely on code with permissive licensing -- a difficult standard to meet, given the lack of transparency when it comes to training data.

Lawsuits involving open source licenses and AI

To date, one major lawsuit has directly addressed claims that generative AI services violate open source software licenses.

The class action suit, colloquially known as the GitHub Copilot Intellectual Property Litigation, was filed in late 2022 by the Joseph Saveri Law Firm and lawyer and open source developer Matthew Butterick. It alleges that Microsoft and OpenAI profited "from the work of open source programmers by violating the conditions of their open source licenses."

In summer 2024, a judge dismissed some of the claims, reasoning that AI-generated code is not identical to the open source code it was trained on and thus does not violate U.S. copyright law, which generally applies only to identical or near-identical reproductions. OpenAI was also dropped from the case at that time.

Later, the plaintiffs appealed, asking the court to clarify that derivative works need not be identical to infringe copyright. As of spring 2025, litigation remains ongoing. Other legal questions -- how much AI-generated code a developer could use before breaching open source licenses, how similar AI-generated code must be to the original to trigger license obligations -- are currently unresolved.

Another closely watched case, although not centered on open source software, could set a relevant precedent. The New York Times filed a lawsuit against Microsoft and OpenAI in late 2023, alleging that the companies violated its copyrights by training AI models on Times content without permission. The Times case, like the GitHub Copilot case, is pending, with both cases surviving motions to dismiss but no clear signal of how courts will ultimately rule.

If the court sides with the Times, the ruling could imply that output generated by AI models trained on certain data qualifies as reuse of that data. Such a finding would mean that copyright or licensing terms that apply to the original data would also apply to data generated by the AI model. This would likely support claims that generative AI violates open source software licenses when trained on and reproducing open source code.

Navigating uncharted terrain

The lack of legal precedent leaves open source communities, AI developers and software engineers using AI tools with little guidance on how to proceed. Nonetheless, each group can take certain steps to protect its interests.

Perhaps the most clear-cut strategy for open source communities is to create licenses that transparently and explicitly state how developers of generative AI models can and can't use their code for model training. The open source space has a long history of adapting its licensing strategies to keep pace with technological change, and AI is just the newest chapter in that story.

AI developers, for their part, can be more transparent about when and how they use open source code in training data sets. They should also be prepared to retrain their models without open source code inputs if courts find that doing so violates licenses. It would be bad news for vendors like Microsoft and OpenAI if GitHub Copilot and similar tools suddenly became unusable due to licensing infringement.

As for developers who rely on generative AI coding tools, it's worth considering tracking which parts of the codebase were produced using AI. Should it become necessary to remove AI-generated code to avoid open source licensing violations, this traceability will be crucial.

Developers might also want to limit their reliance on AI-assisted coding tools until the legal landscape becomes clearer. For those seeking faster ways to generate code without starting from scratch, traditional low-code and no-code tools might be a safer alternative, as they typically don't incorporate LLMs and therefore raise fewer licensing concerns.

Chris Tozzi is a freelance writer, research adviser, and professor of IT and society who has previously worked as a journalist and Linux systems administrator.