Advantages and disadvantages of AI explained

Is AI good or bad? AI will benefit society, according to experts, but only with the correct guidelines in place and a solid understanding of what AI systems can and cannot do.

AI touches nearly all organizations and an increasing number of individuals in their day-to-day lives, raising questions about the impact of AI on users, the extent of changes being wrought by AI and whether AI brings more problems than benefits.

A 2024 survey conducted by Public First in partnership with the Center for Data Innovation highlighted divided sentiment around AI.

Among the 2,000-plus U.S. adults surveyed, large majorities of Americans expressed interest in using AI for a variety of personal purposes, including learning new information (73%), reducing energy usage (66%), and managing health and fitness (60%).

But when asked if AI will be good or bad for them personally, only 32% said it will make things better, and 22% said it would make things worse. Meanwhile, 33% said it would have no impact. Moreover, negative feelings about AI increased since last year, with 37% of respondents expressing worry (up from 32%), 28% feeling anxious about AI (up from 23%) and 23% reporting they were scared (up from 19% in 2023).

On the business side, data shows that executive embrace of AI is nearly universal. A 2024 "AI Report" from UST, a digital transformation software and services company, found that 93% of the large companies it polled said AI is essential to success.

This article is part of

What is enterprise AI? A complete guide for businesses

Yet enterprise leaders are also weighing the benefits and drawbacks of AI. They're reporting productivity and efficiency gains, but they're also grappling with data privacy, security and ethical challenges as they deploy AI in their organizations.

What are the benefits of AI?

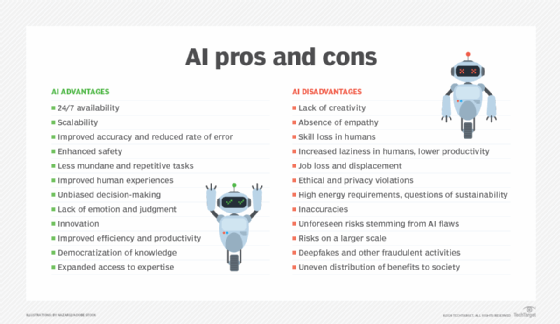

By nearly all accounts, AI comes with both advantages and disadvantages, which individuals and organizations alike need to understand to maximize the benefits this technology brings while mitigating the negatives.

Benefits of AI include the following.

1. 24/7 availability

AI's 24/7 availability is one of its biggest and most cited advantages. Other computer technologies can operate around the clock too. Companies have benefited from the high availability of such systems, but only if humans have been available to work with them. According to multiple experts, AI's ability to make decisions and take actions without human involvement in many business circumstances means the technology can work independently, ensuring continuous operations at an unprecedented scale.

2. Scalability

AI not only works continuously but also scales almost infinitely. "With AI, you can scale to a level you never could have before," said Seth Earley, founder and CEO of Earley Information Systems and author of The AI-Powered Enterprise.

The personalized recommendations that companies such as Amazon and Netflix offer to their customers are a case in point. While a salesclerk who works often enough with a customer might be able to extend such services to that individual, AI can do so for hundreds of thousands of customers at the same time by analyzing available customer data. AI similarly demonstrates this scalability in the financial industry, where institutions use the technology to instantly verify and validate millions of transactions and monitor for potential fraud every day.

3. Improved accuracy and reduced rate of error

Unlike humans, AI systems don't get tired or become distracted. They're able to process infinitely more information and consistently follow the rules to analyze data and make decisions -- all of which make them far more likely to deliver accurate results nearly all the time.

"Because AI does not rely on humans, with their biases and limitations, it leads to more accurate results and more consistently accurate results," said Orla Day, CIO of educational technology company Skillsoft.

There's a big caveat here, however. To deliver such accuracy, AI models must be built on good algorithms that are free from unintended bias, trained on enough high-quality data and monitored to prevent drift.

4. Enhanced safety

AI is used for real-time monitoring and hazard detection. The technology can be trained to recognize normal and/or expected machine operations and human behavior. It can detect and flag operations and behaviors that fall outside desired parameters and indicate risk or danger. Such AI use has improved safety records in multiple industries and scenarios.

AI's ability to improve safety is evident in motor vehicle features that warn drivers when their attention wanes or they drift out of their travel lane. AI's safety-enhancing capabilities are also seen in manufacturing, where it is deployed to automatically stop machinery when it detects workers getting too close to restricted areas. It's also on display when AI-powered robots are used to handle dangerous tasks, such as defusing bombs or accessing unstable buildings, instead of humans.

5. Performs mundane and repetitive tasks

Experts also credit AI for handling repetitive tasks for humans both in their jobs and in their personal lives. As more and more computer systems incorporate AI into their operations, they can perform an increasing amount of lower-level and often boring jobs that consume an individual's time. Everyday examples of AI's handling of mundane work include robotic vacuums in the home and data collection in the office. That, in turn, leaves humans with more time for higher-value tasks.

"This is where we see the biggest ROI right now, and it's where most companies are using AI: to reduce the amount of time that people need to spend on such activities," said Claudio Calvino, senior managing director of the data and analytics practice at FTI Consulting.

6. Improved human experiences

AI analyzes vast volumes of data to identify specific patterns, a capability that organizations use to deliver services in a highly personalized fashion. For example, Daly said her company, Skillsoft, is using AI to deliver more content customized to individual customers much faster than human employees could do. Her company is hardly alone in its use of AI to create better experiences for customers and employees: The "Global AI & Digital Experience Survey 2024" from technology company Riverbed found that 94% of surveyed enterprise leaders said that AI will help them deliver a better digital experience for employees and end users.

7. Unbiased decision-making

AI takes emotion, guess work, intuition and personal experience out of decision-making and instead uses data and mathematical algorithms to identify the best course of action, explained Antino Kim, associate professor of operations and decision technologies at Indiana University's Kelley School of Business. As such, AI theoretically can remove human biases from the process -- if the algorithms and data that AI systems use are themselves free from bias. However, even then, AI might not be foolproof, as it can produce inaccurate results as well as made-up responses, known as hallucinations.

8. Lack of emotion and judgment

Similarly, AI itself does not have any human emotions or judgment, making it a useful tool in a variety of circumstances. For example, AI-enabled customer service chatbots won't get flustered, pass judgment or become argumentative when dealing with angry or confused customers. That can help users resolve problems or get what they need more easily with AI than with humans, Kim said.

He said research has found, for example, that students sometimes are more comfortable asking chatbots questions about lessons rather than humans. "The students are worried that they might be judged or be [thought of as] stupid by asking certain questions. But with AI, there is absolutely no judgment, so people are often actually more comfortable interacting with it."

9. Innovation

AI is fueling advances across multiple industries as well as functional areas, such as supply chain operations. Moreover, it is expected to spur even more innovations in the future.

"AI is bringing massive improvements; it is a gamechanger," Johnson said. As an example, he pointed to AI's use in drug discovery and healthcare, where the technology has driven more personalized treatments that are much more effective.

10. Improved efficiency and productivity

Individuals and organizations are finding that AI provides a significant boost to their efficiency and productivity, said Zhe "Jay" Shan, assistant professor of information systems and analytics at Miami University Farmer School of Business. He highlighted how generative AI (GenAI) tools, such as ChatGPT and AI-based software assistants such as Microsoft's Copilot, can shave significant time off everyday tasks.

Look at how AI is changing software development, for example. Coders can use GenAI to handle much of the work and then use their skills to fine-tune and refine the finished product -- a partnership that not only saves time but also allows coders to focus on where they add the most value.

"I don't think it's about man versus machine. It's more about using AI technologies to augment and improve performance. That's where the power is," said Arnab Bose, chief scientific officer at UST AlphaAI, a digital transformation software and services company.

11. Democratization of knowledge

As AI becomes more accessible, it also facilitates access to more knowledge for more people and helps more people make sense of information that was once only the domain of experts, Johnson said.

Look at software development again. AI tools enable more people to learn how to code. But they also enable individuals to produce software code without having to know how to code. Johnson said organizations benefit here, too, as they can use AI to collect, catalog, archive and then retrieve institutional knowledge held by individual workers, thereby ensuring it is accessible to others.

12. Expanded access to expertise

AI-powered computer systems are being built to perform more and more expert and specialized services -- something that will make such services accessible to people and businesses that could not easily access them in the past.

Take, for instance, AI's ability to bring big-business solutions to small enterprises, Johnson said. AI gives smaller firms access to more and less costly marketing, content creation, accounting, legal and other functional expertise than they had when only humans could perform those roles. This, he noted, gives solo practitioners and small shops the ability "to execute high-caliber business operations."

What are the disadvantages of AI?

Using AI to advantage hinges on knowing the technology's principal risks, said Eric Johnson, director of technology and experience at West Monroe, a digital services firm.

"AI is a landscape that is fraught with both significant opportunities and significant risk," Johnson said, "and that [relates to] the ability of an organization to leverage these tools from not only a technical implementation perspective but also a user and change management perspective."

Frequently cited drawbacks of AI include the following.

1. Lack of creativity

Although AI has been tasked with creating everything from computer code to visual art, AI is unlike human intelligence in that it lacks original thought. As experts have noted, AI has what's considered narrow intelligence. It knows what it has been programmed and trained to know; it is limited by its own algorithms and what data it ingests. AI essentially makes predictions based on algorithms and the training data it has been fed. Although machine learning algorithms help the machine learn over time, it doesn't have the capacity humans have for creativity, inspiration and new ways of thinking.

"I've seen people use AI to create garbage. It lacks any personality. It lacks any voice. You want to immediately ignore it," Earley said.

2. The absence of empathy

AI can be taught to recognize human emotions such as frustration, but a machine cannot empathize and has no ability to feel. Humans can, giving us a huge advantage over unfeeling AI systems in many areas, including the workplace.

"Since AI is not human, it doesn't have genuine connections. So that empathy -- that ability to truly understand -- is lacking," Kim said.

3. Skill loss in humans

Although experts typically list AI's ability to free people from repetitive and mundane tasks as a positive, some believe this particular benefit comes with a downside: a loss of skills in people. "You're going to start seeing a gradual loss of critical skills and critical thinking," Earley said.

He cited the loss of navigational skills that came with widescale use of AI-enabled navigation systems as a case in point. Skill loss is happening not just in navigation, he and others said, explaining that people typically advance their knowledge and expertise as well as their personal and professional crafts by first learning and mastering easy repetitive tasks. That mastery of the basics then allows them to understand how those tasks fit into the bigger parts of the work they must accomplish to complete an objective.

But as AI takes over those entry-level jobs, some have voiced concerns that people could lose their ability to know and understand how to perform those tasks. That could stymie their ability to truly master a profession or trade. It could also leave them without the necessary capabilities to step in and perform the work should the AI fail.

4. Increased laziness in humans and lower productivity

Similarly, a contingent of thought leaders have said they fear AI could enable laziness in humans. They've noted that some users assume AI works flawlessly when it does not, and they accept results without checking or validating them.

Meanwhile, Earley said AI use sometimes causes a drop in productivity, explaining that AI -- GenAI in particular -- can produce outcomes that take people longer to verify, refine or validate than it would have taken for them to do the work from start to finish themselves. This is particularly noticeable in cases when the AI is not well-suited to the task.

"People tend to overuse AI or use it improperly," Earley added.

5. Job loss and displacement

According to the 2024 report titled "Leading through the Great Disruption" from Switzerland-based global talent firm Adecco Group, 41% of the 2,000 C-suite executives surveyed said they will employ fewer people within five years because of AI. Only 46% said they will redeploy employees whose jobs are lost due to AI.

An April 2023 report from Goldman Sachs Research estimated that AI "could expose the equivalent of 300 million full-time jobs to automation." The authors also estimated "that roughly two-thirds of U.S. occupations are exposed to some degree of automation by AI."

The story is complicated, though. Economists and researchers have said many jobs will be eliminated by AI, but they've also predicted that AI will shift some workers to higher-value tasks and generate new types of work. Existing and upcoming workers will need to prepare by learning new skills, including the ability to use AI to complement their human capabilities, experts said.

6. Ethical and privacy violations

As AI use becomes more widespread, so do the risks of ethical and privacy violations.

"There is no shortage of concerns," Daly said. She and others said AI presents a number of ethical issues, from the presence of bias in a system to a lack of explainability, where no one understands how exactly AI produced certain results.

Similarly, many are concerned about how to protect sensitive data in the era of AI. Experts noted that AI systems' use of data could expose proprietary or legally protected data in ways that run afoul of laws, regulations, corporate best practices and consumer expectations.

7. High energy requirements and questions of sustainability

The compute power required for AI systems is high, and that's driving explosive demands for energy. The World Economic Forum noted as much in a 2024 report, where it specifically called out generative AI systems for their use of "around 33 times more energy to complete a task than task-specific software would."

Although AI can and already is being used to help organizations develop more sustainable practices, some experts have expressed concerns that AI's energy needs could hurt more than help sustainability efforts, particularly in the short term.

8. Inaccuracies

"AI can be wrong," Bose said. "At the end of the day, AI is a statistical machine. It's working on probabilities. The number of times it gets things wrong is very, very small, but it's not zero."

9. Unforeseen risks stemming from AI flaws

AI users have found that they face new risks because of their AI use, with the most notable risk stemming from AI offering inaccurate results or producing hallucinations.

One notable incident happened in 2023, when a New York lawyer faced judicial scrutiny for submitting court filings citing fictious cases that had been made up by ChatGPT. The lawyer acknowledged using ChatGPT to draft the document and told a federal judge that he didn't realize the tool could make such an error.

10. Risks on a larger scale

Organizations have always had to contend with risk. But they now face exponentially higher risk with AI, with its ability to operate 24/7 and to operate at an unprecedented scale. AI can dramatically amplify one error in the algorithm or the data it uses.

"The nature of the risk hasn't changed, but the magnitude and the scale of the risk has. It's at a much larger scale," Calvino said.

11. Deep fakes and other fraudulent activities

Hackers, schemers and others are using AI to further their nefarious activities. They're using the technology to craft and launch increasingly sophisticated phishing emails and other cyberattacks. They're using AI to impersonate others. They're using it to create deep fakes -- audio and/or visual content that seems real but isn't -- to trick others.

"All of these are problems," Johnson said. "And as long as people are fooled into thinking this is real content, it will be a problem."

12. Uneven distribution of benefits to society

Many experts expect that the benefits of AI will outweigh the downsides. However, Earley said he does not expect that to be the case for everyone. He predicted that the gains brought by AI will be unevenly distributed and that some people will be more negatively impacted than others.

"I think AI will bring a net improvement in many areas, but there will be losers in society," Earley added.

Examples of good AI use cases

AI has enabled significant advances in many areas of society. The following use cases illustrate the positive side of this technology:

- Khan Academy, a nonprofit educational organization that provides free learning tools, announced in 2024 that it made its AI teaching assistant named Khanmigo free for every US educator to use. The aim is to help teachers reduce the amount of time they spend on preparation, such as generating rubrics and developing quiz questions, so they have more time for teaching.

- Newer model cars use AI-enabled systems to ensure safety on the road by monitoring blind spots; alerting drivers when their attention wanes; and taking preventative measures, such as braking automatically to avoid crashes.

- Swiss researchers announced in spring 2023 that they used AI as part of a medical treatment plan to help a paralyzed man walk for the first time in 12 years.

Examples of bad AI use cases

Although AI itself is a neutral entity, its use in some circumstances demonstrates its limits and potential to harm others. These real-world examples demonstrate how AI can be inappropriately used:

- Scammers used AI to impersonate a company's CFO, creating a deepfake that was so convincingly real that they got a finance worker at the company to pay out $25 million.

- During Google's early 2023 demonstration of its generative AI chatbot named Bard -- now known as Gemini -- Bard erroneously stated that the James Webb Telescope "took the very first pictures of a planet outside of our own solar system." Such images predated the telescope's launch by 16 years. Shares in Google's parent company, Alphabet, dropped nearly 8%, or about $100 billion, in the aftermath of the public error.

- In early 2024, a British Columbia tribunal found Air Canada liable for misinformation that its chatbot provided to a customer and awarded about $800 in damages to the plaintiff. Air Canada had tried to disavow its responsibility for the chatbot that provided erroneous information about the company's policy on bereavement fares. But the tribunal's decision indicated that a company is accountable for the actions of its AI systems.

Mary K. Pratt is an award-winning freelance journalist with a focus on covering enterprise IT and cybersecurity management.