surveillance capitalism

What is surveillance capitalism?

Surveillance capitalism is the monetization of data captured through monitoring people's movements and behaviors online and in the physical world. Consumer surveillance is most commonly used for targeted marketing and advertising.

The term surveillance capitalism was first introduced by John Bellamy Foster and Robert W. McChesney in July 2014, in Monthly Review, a New York socialist magazine. Their concept of surveillance capitalism focused on the U.S. military and surveillance of citizens.

The term is more closely associated with an economic theory Harvard Business School Professor Emerita Shoshana Zuboff proposed in September 2014. It describes the modern, mass monetization of individuals' raw personal data to predict and modify their behavior. In her 2019 book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, Zuboff defines surveillance capitalism as a "new economic order that claims human experience as free raw material for hidden commercial practices of extraction, prediction, and sales."

Big tech companies like Amazon, Apple, Google and Facebook use surveillance capitalism to collect users' personal data. Such data includes search histories, social media posts, physical locations and product keywords captured by microphones in smartphones and internet of things (IoT) devices. The data is packaged into prediction products that are sold to companies for use in targeted marketing and behavioral marketing purposes.

These prediction products enable businesses to market and advertise to the people most likely to buy their products and services. According to Zuboff, individuals whose data is collected and monetized this way often aren't aware of it or do not have the option of consenting to its collection and sharing without forfeiting the functionality of their devices.

Zuboff pegged the beginning of surveillance capitalism to the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. After those happened, the United States expanded mass surveillance with laws such as the Patriot Act and encouraged the data gathering activities of companies like Google through lenient regulations, she said.

In her book, Zuboff credited Google and Google AdWords with creating surveillance capitalism in 2001 when it began selling its surplus consumer data to advertisers without informing users. This created a new asset class of raw material data without incurring any additional margin costs. This approach became the surveillance capitalist business model for other tech companies.

How surveillance capitalism works?

Companies using the surveillance capitalism model follow these three steps, according to Zuboff:

- Data collection. They collect surplus data obtained from an individual's interactions with digital devices, websites and applications. This is data that doesn't have a direct relevance to an individual's use of a digital device or service but is a byproduct of that use. It can include information such as the physical location of a user, search history and habits like the time of day an individual exercises.

- Prediction products. The data is fed into advanced machine intelligence manufacturing processes that use artificial intelligence technologies to fabricate prediction products that are able to anticipate what a person will do now, soon and later.

- Behavioral markets. Companies sell these products in a new kind of marketplace for behavioral predictions that Zuboff referred to as "behavioral futures markets." Businesses in these markets include insurance, retail, finance and an expanding economic sector of e-businesses. These companies use the prediction products to target their goods and services at likely customers and perform behavioral modification. Behavioral modification attempts to influence an individual's behavior through subtle suggestions. For instance, some insurance companies use behavioral underwriting to automatically raise insurance rates depending on a driver's behavior.

In Zuboff's analysis, no piece of information technology inherently breaches data privacy. Surveillance capitalism is not an inevitable part of the use of digital technology but rather a business philosophy. For instance, surveillance capitalists often only allow access to their devices, services and software updates if users sign agreements allowing the owners to collect and share the users' data with unspecified third parties.

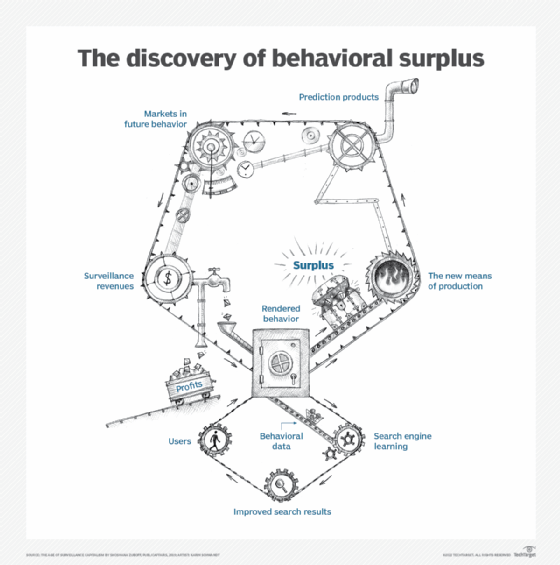

"Although some of these data are applied to product service improvement, the rest are declared as a proprietary behavioral surplus," she said. This means any personal data a company collects from a user's interaction with its service is the property of the company, not the user.

Key features of surveillance capitalism

In The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Zuboff summarizes the economic logic and operations of surveillance capitalism with four key features and uses Google as her example:

- Logic. The logic, or philosophy, underlying surveillance capitalism is like industrial capitalism. Just as industrial capitalism transforms nature's raw materials into commodities, surveillance capitalism uses human nature for new commodity inventions. Users are no longer the primary customers but merely the "objects from which raw materials are extracted," while the real customers are advertisers and other companies who buy surveillance capitalists' prediction products, Zuboff said. This leads to the "rendering of our lives as behavioral data for the sake of others' improved control over us," she added.

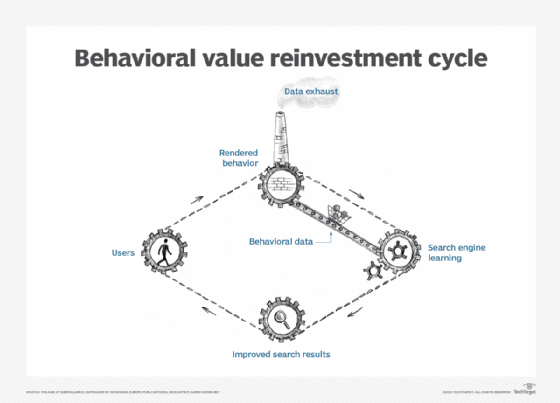

- Means of production. The means of production for surveillance capitalists like Google are algorithms that predict a user's behavior based on all known data about them. These machine learning algorithms become more accurate and lucrative predictors the more data they have access to, leading to an ever-increasing scope of surveillance.

- Products. Surveillance capitalism's prediction products are based on collected data. According to Zuboff, companies like Google use the fact that they manufacture and sell prediction products and not the raw data itself to claim they do not sell user data at all.

- Marketplace. The early buyers in the behavioral futures marketplace were advertisers. However, customers have expanded to "any actor with an interest in purchasing probabilistic information about our behavior and/or influencing future behavior." This includes insurance businesses, political consulting firms such as Cambridge Analytica, and any organization interested in predicting the likely behaviors of individuals.

Data markets' effect on surveillance capitalism

According to Zuboff, competition in surveillance capitalism's data markets, or behavioral futures markets, is based on predicting individuals' behavior with the certainty. Over time, this competition, combined with the increased technological capabilities of data collection, has led companies to pivot from simply predicting individuals' behavior to trying to modify it.

This is a fundamental evolution in capitalism. "As long as surveillance capitalism and its behavioral futures markets are allowed to thrive, ownership of the new means of behavioral modification eclipses ownership of the means of production as the fountainhead of capitalist wealth and power in the twenty-first century," Zuboff said.

The practice of behavioral modification already extends to political behavioral modification. As an example, Zuboff pointed to the 2016 Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal in which Facebook was found to have sold user data to British consulting firm Cambridge Analytica. This data included the results of Facebook users' personality tests that Cambridge Analytica used to target Facebook users with political advertising.

Future of data collection

There are no serious proposals for regulating the data collecting abilities of technology companies. However, Google did pay a large data privacy settlement in November 2022.

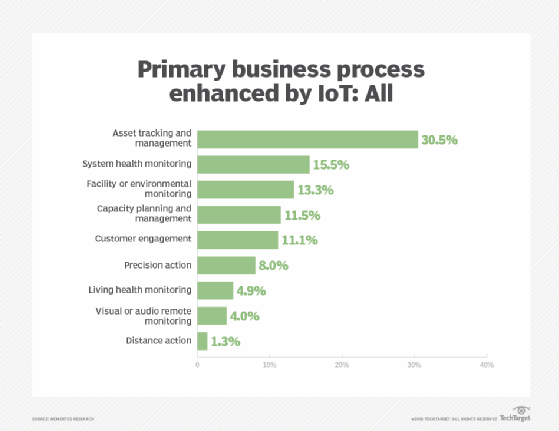

In her book, Zuboff predicted data collection will continue to expand the more it drives the overall market and the more technology is integrated into daily life. She noted that the use of IoT devices, such as fitness trackers, is increasing along with opportunities for sharing data with marketers and advertisers.

Zuboff also mentioned a 2016 Microsoft patent for software that can detect users' mental states. This application would violate privacy on an unprecedented level by activating sensors to record voice and speech, videos and images, and movement, she said.

People accept surveillance capitalism because they often don't know the extent of the data collection that various tech providers are doing, and they depend on the digital technologies they're using. However, according to Zuboff, these trends could have serious consequences for the digital future:

- ending the right to privacy as a social norm;

- reducing the ability of individuals to control their digital lives; and

- weakening human autonomy and possibly democracy.

Surveillance capitalism is the growing business model of big data and e-commerce. Learn more about the processes, challenges and best practices of big data collection.