wiretapping

What is wiretapping?

Wiretapping is the surreptitious electronic monitoring and interception of phone-, fax- or internet-based communications. A typical eavesdropping activity involves connecting to phone lines and using a monitoring device to listen in on phone conversations.

Wiretapping is achieved either through the placement of a listening device -- often referred to as a bug -- on the wire in question or through built-in mechanisms in other communication technologies.

Law enforcement officials or nefarious actors can use either approach for live monitoring or recording. Packet sniffers are programs used to capture data being transmitted on a network. They're a commonly used wiretapping tool. A variety of other tools are available for various applications.

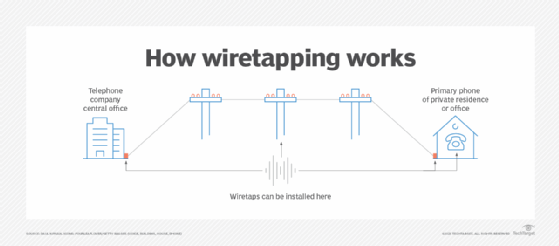

Wiretaps for phone calls can be installed in a telephone company's central office, on telephone poles and even on telephone lines at the connection point from the outside into a home or office. Bugs can also be installed in a device. More sophisticated surveillance systems are used when monitoring computer networks and information systems.

How is wiretapping used?

The goal of wiretapping is to establish a surreptitious connection to an information system or network for collecting information. In the U.S., a warrant is needed to establish a legal wiretap. In most cases, wiretapping is illegal. Some of the ways wiretapping is used include the following:

- Law enforcement. The police and other law enforcement agencies use wiretapping to collect information about illegal activities. Data collected from a wiretap for a criminal case is admissible in court if the wiretap was legally sanctioned.

- National security. The Central Intelligence Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other government agencies can use wiretaps under certain circumstances where they can demonstrate that national security is at risk.

- Threat actors. Criminal elements use wiretapping to gather information about a person or organization to cause damage in various ways.

- Commercial espionage. Businesses use wiretapping to obtain information about competitors. The legality of such use can vary depending on the jurisdiction. In most countries, wiretapping is subject to strict regulations and typically requires authorized consent or a court order. However, it is important to note that laws can differ among countries.

Can cell phone calls be wiretapped?

Cell phone calls can potentially be listened to under certain circumstances. A few scenarios where cell phone calls can potentially be intercepted include the following:

- Authorized Interception. Law enforcement agencies, with the appropriate legal authorization such as a warrant, can intercept and listen to cell phone calls as part of criminal investigations.

- Surveillance by malicious actors. Bad actors may attempt to intercept cell phone calls through illegal means, such as using spyware or modified devices. These methods can potentially grant unauthorized access to call data and conversations.

The general risk of eavesdropping on cell phone calls is relatively low. Measures can be taken to bolster security, such as using communication applications that employ end-to-end encryption and regularly updating devices with the latest security patches.

Wiretapping and privacy laws

Wiretapping laws must balance the privacy rights of individuals with the concerns of the state and law enforcement officers. The two main legal areas affecting attempts to intercept communication in this way are wiretapping laws and privacy laws.

Wiretapping laws

Wiretapping laws vary by country and jurisdiction. These laws typically outline the circumstances under which wiretapping is permissible, such as for law enforcement or national security purposes. Businesses engaging in wiretapping must adhere to these laws and obtain the necessary legal authority and consent when applicable.

In the U.S., federal laws govern wiretapping, and each state has its own laws and regulations that complement or further define the federal statutes. Most state wiretapping laws are modeled after the federal Wiretap Act. These state laws generally criminalize the secret audio recording or interception of private communications. However, there may be variations in the specific provisions, requirements and penalties across different states.

Privacy laws

Wiretapping usually involves the interception of private communications, making privacy laws a crucial consideration. Privacy laws protect an individual's right to privacy and might require businesses to obtain explicit consent from individuals before engaging in any wiretapping activities. Business owners must be aware of and comply with the privacy laws that apply in the jurisdictions where they operate.

The history of wiretapping

Wiretapping has existed since the days of the telegraph. During the Civil War, both Union and Confederate soldiers engaged in tapping into enemy telegraph lines. The first recorded wiretapping by law enforcement was in the 1890s in New York City.

In the 1910s, the New York State Department of Justice found that police had wiretapped hotels without warrants. The department claimed this wiretapping didn't violate Fourth Amendment protection from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government on the grounds that the amendment only covers tangible communications, such as mail, and that it only breached those rights when the placing of taps involved trespassing. That restriction didn't block enforcement because law enforcement could place a tap in a telephone company's switching central office.

The exemption of intangibles from the Fourth Amendment was upheld with the conviction of Roy Olmstead -- a former prohibition police officer turned multimillionaire bootlegger -- in 1925. However, the case subsequently went to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. There, Justice Frank H. Rudkin unsuccessfully fought for the requirement of a warrant for wiretapping, claiming the distinction between written messages and telephone was tenuous and that letter, telephone and telegraph were equally sealed from the public and deserved the same protections.

The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1928. The Court found in a 5-to-4 decision that the constitutional rights of a wiretapping target hadn't been violated. In his dissent, Justice Louis Brandeis contested the allowance of wiretaps without a warrant, stating that the Fourth Amendment isn't about defining physical space but the rights of the individual.

The debate continued until 1968 when the Crime Control and Safe Streets Act mandated probable cause for individual warrants and the requirement that the monitored party be notified after the conclusion of the investigation.

Modern-day wiretapping laws

As cell phones and other telecommunication technologies, such as email and text messages, emerged throughout the 20th century, arguments were made that they weren't covered by existing wiretap laws, often to justify increased monitoring of private citizens. New laws were enacted in the latter half of the previous century to clarify these issues, including the following:

- Wiretap Act of 1968. This law prohibited any kind of electronic communications surveillance without a court order or warrant

- Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986. ECPA includes the Stored Wire Electronic Communications Act and superseded the Wiretap Act. It loosened the requirements for wiretapping hard-wired and nonwired communications.

- Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act of 1994. CALEA updated the ECPA by requiring telephone companies to build their networks with wiretapping technology and surveillance capabilities. Carriers must file and regularly update system security and integrity plans with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that describe how they will comply with CALEA requirements. The FCC doesn't specify how carriers provide surveillance capabilities in their networks. As such, carriers may develop their own solutions for CALEA compliance, obtain surveillance technology from a vendor or purchase a solution from a trusted third party.

The National Security Agency's monitoring of private citizen communications has raised concerns since it was revealed in 2013 that the agency was engaged in wiretapping without a stated justification. The NSA program, in operation since 2001, collects metadata rather than the content of messages, but even metadata can be extremely revealing.

Wireless computer networks provide all sorts of opportunities for intercepting communications. Learn about some common wireless network attacks, such as packet sniffing and rogue access points, and how to prevent them.