What is security theater?

Security theater refers to highly visible security measures that create the illusion of increased safety but don't stop threats. The term is often used disparagingly to describe superficial security practices that don't reduce risk. Simply put, security theater is all about appearances, not results.

Security theater is often used as a stopgap measure after a crisis to provide people with a sense of increased safety until more effective security solutions can be implemented. The problem is that security theater requires high visibility, and the attention this type of security control requires can make people think security gaps are being addressed. Meanwhile, the vulnerabilities that led to the crisis remain exposed.

Bruce Schneier and security theater

The term security theater is credited to Bruce Schneier, a well-known American technologist and computer security professional. In his 2003 book, Beyond Fear, Schneier provided examples of highly visible security measures designed to make people feel more secure and referred to them as "security theater." He wrote, "It's important to understand security theater for what it is, but not to minimize its value. Security theater scares off stupid attackers and those who just don't want to take the risk."

It wasn't long before the phrase security theater became a popular topic in the press, and the term became closely linked to airport security in the U.S. The media often highlighted the inefficacy and absurdity of certain Transportation Security Agency security measures and rarely -- if ever -- acknowledged their potential value as a deterrent.

For a while, it seemed like Schneier also forgot that security theater has any value. In 2009, he wrote an essay entitled "Beyond Security Theater" and reminded readers that security measures "are largely invisible" and security theater "consumes resources that could better be spent elsewhere."

More recently, however, Schneier proposed that security theater is being driven by a concept in economics called information asymmetry. Putting that in the context of cybersecurity, Schneier said it means "people who don't understand security can be reassured with cosmetic or psychological measures." He also said, "Sometimes that reassurance is important" and used infant bracelet systems in hospitals to illustrate his point.

Schneier's work is important because his books, articles and blog posts have helped IT professionals recognize that security is not just a technical concern, but it also has psychological, political and economic aspects that shouldn't be ignored. Schneier's acknowledgement that security theater can have value in some scenarios -- as long as it doesn't replace measurable controls or consume disproportionate resources -- has also helped encourage a greater appreciation for layered defense strategies in IT.

Examples of security theater

Here are some classic examples of security theater in IT:

- Installing security cameras or badge readers but not connecting them to anything.

- Prioritizing bug fixes by their Common Vulnerability Scoring System rating instead of their risk to the organization.

- Forcing users to create strong passwords and change them frequently without providing support for two-factor authentication.

- Producing lengthy policy documents to satisfy regulatory compliance requirements but never enforcing the policies.

- Mandating security awareness training once a year to meet compliance requirements but not following up to see if everyone has completed training.

- Hiring a uniformed guard to check visitor IDs instead of deploying a visitor management platform.

Each of these examples can appear to be improving security at first glance, but in reality, they are just window dressing. For example, a threat actor could easily follow an authorized individual through an access-controlled door to avoid a visitor management system kiosk. Or an employee who's required to change their password each month could get fed up and start writing their passwords down to make life easier.

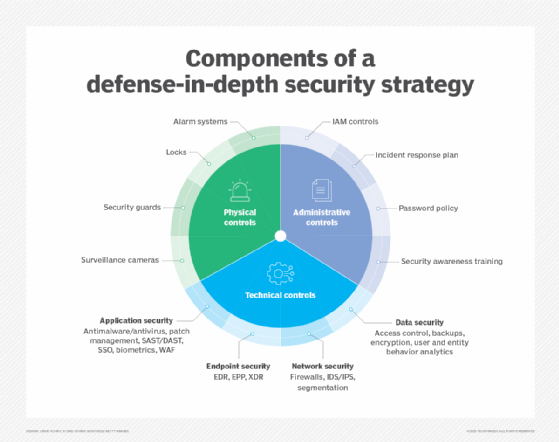

Even so, it's important to acknowledge that security theater isn't inherently bad. While its effectiveness can't be measured or validated easily, its use can still be beneficial when used in conjunction with measurable security controls and treated as an ancillary component of a defense-in-depth strategy.

Security theater in cybersecurity

In cybersecurity, security theater may also be referred to as performative security or performative-based security. Both terms still describe highly visible security measures that are implemented primarily for show, but using the word performative instead of theater emphasizes the intent behind the action rather than the dramatics of the display.

Arguably, regulatory compliance is one of the most visible arenas for security theater in cybersecurity. Regulations like General Data Protection Regulation and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act require organizations to demonstrate that they have appropriate security controls in place. Unfortunately, because compliance is often enforced through audit checklists and reports, some organizations may focus more on what looks good on paper instead of on what reduces risk.

In real life, this can have serious consequences. For example, an insurance provider might pass a compliance audit by documenting it has access control policies and antivirus software in place but still suffer a major data breach if those controls are poorly configured, outdated or not actively monitored.

The psychology behind security theater

While security processes can be measured with risk analysis and threat modeling, security theater is rooted in psychology and can only be measured subjectively. It prioritizes people's perception of reality in hopes that what they perceive is what they believe.

People often respond emotionally to perceived threats, even when those fears are out of proportion to risk. Media exposure, personal experience and cognitive biases can shape which threats seem most pressing, regardless of their statistical likelihood. For example, a chief financial officer who works for a healthcare company might be more fearful of ransomware attacks after reading a high-profile news story, even if their own organization faces a greater risk from denial-of-service attacks.

Visual security barriers can be surprisingly effective at making people feel safer, which helps explain why security theater remains a useful tool. In some cases, the psychological effects can serve a useful purpose by calming public anxiety or reducing the spread of panic. However, this false sense of security can backfire and lead to complacency, reduced vigilance and increased vulnerability to threats.

Understanding the psychological dynamics behind security theater is essential for allocating resources and balancing reassurance with effective, evidence-based protection.

Effect of security theater

As Bruce Schneier has pointed out, some of the measures that constitute an organization's security theater may have a slight benefit to security. But, ultimately, they are more about making individuals feel better. Security theater is all about creating an illusion of safety and promoting a false sense of protection.

Most security theater offers little -- and, in some cases, no -- protection from threats, and serious warning signs may go unnoticed and remain unaddressed until it's too late. This can put organizations at risk for many kinds of cyberattacks and subsequent consequences, like financial losses, erosion of customer trust and regulatory fines.

Organizations that put too much focus on security theater can get distracted from the necessary work: implementing adequate security defenses to prevent cyberattacks and mitigate their effect. They may become complacent and assume that their existing measures provide enough protection and that stronger defenses are not required. Such ignorance can create dangerous blind spots, leave critical vulnerabilities unaddressed and increase the risk that cyberattacks are successful.

Security theater can also waste enterprise resources -- both people and money. When too many resources are used for pomp and show, it can reduce available resources for other security initiatives that could strengthen the organization's security posture.

How to identify security theater

Identifying security theater requires skepticism, a focus on outcomes rather than activities and an understanding of the organization's threat landscape. In other words, it means asking: Does this security measure genuinely reduce risk against likely threats, or does it merely look like it does?

One way to get the answer to this question is to try and measure effect. If a security control's effectiveness can't be measured and there's no qualitative evidence of its effect, that's a red flag.

Penetration tests can also be used to weed out security theater. Pen tests can simulate real-world attacks on an organization's systems, networks or applications. If a security control doesn't issue an alert during a breach simulation, it could be because the control is just security theater.

Boost your organization's cybersecurity by adopting best practices to protect your infrastructure and ensure quick recovery after a breach. Also, learn about the differences between pen testing and vulnerability scanning and why both are important for extensive cybersecurity, as well as cybersecurity myths that are putting businesses at risk.